|

Thoughts on Sinofuturism

What does it mean for China to be "the future"? And what does that future look like?

Most discussions that I see about China these days are about U.S.-China competition, or the question of whether China’s economy will reign supreme (my answer: Probably, yes, because it’s really big). But there’s another strain of discourse that’s kind of interesting, which is whether China is the Country of the Future, in terms of technology and urbanism.

In my experience, these discussions are usually pretty vague and confused, jumping back and forth between architecture, transportation, consumer technology, production technology, art, pop culture, soft power, urban design, and a bunch of other topics. That doesn’t mean I think the topic is worthless; vague and confused discussions can be fun! But I thought I’d try to think about Sinofuturism a little more systematically.

As far as I can tell, the recent burst of Sinofuturism seems to come from four main sources:

China’s new high-tech industrial model

The legacy of China’s real estate boom

A charm offensive by China

The election of Donald Trump

In the early 2020s, the economic model that had sustained Chinese economic growth since 2008 basically collapsed. This model was based on massive real estate investment — the biggest development boom in the history of the world. Real estate sales funded local governments, so local governments basically approved and supported any and all development that would increase the value of land. Meanwhile the Chinese central government encouraged banks to lend to developers as a way of sustaining the macroeconomy through a series of shocks. This predictably led to an eventual financial bubble and crash when the loans used to finance this incredible development boom outran the ability of real estate to generate economic returns. There was a big bust in 2021-23, and growth slowed down:

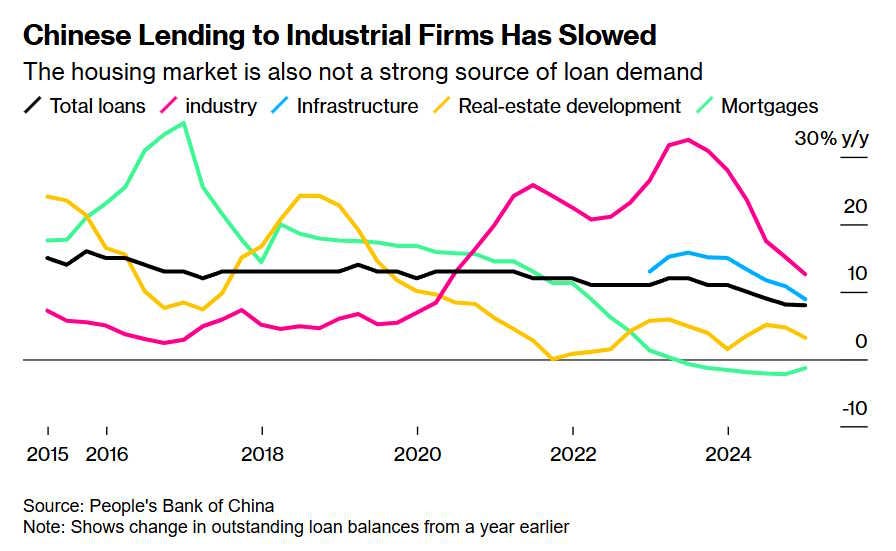

China’s leadership responded to this slowdown by going all-in on high-tech manufacturing. At Xi Jinping’s behest, the country’s banks poured untold amounts of money into sectors like autos, semiconductors, machine tools, robots, electronics, batteries, aircraft, and all kinds of other stuff. The government supported the boom with subsidies as well, though I think we often tend to overemphasize its role relative to the private initiative of companies like BYD, Xiaomi, and DJI.

That lending boom has since cooled off a bit, but it was enormous during 2021-23, and industrial loans continue to grow at a fairly rapid clip:

|

All that lending fueled a wave of investment in the “technologies of the future”. Many of those were production technologies — the machine tools and robots in the highly automated Chinese factories that you can see in videos like this one:

And some are consumption technologies, like the high-speed rail network that’s bigger than all the networks in the rest of the world combined:

This tech boom won’t be enough to return the country to pre-Covid levels of growth.¹ But it has transformed Chinese cities, filling them with futuristic stuff like delivery drones, drone shows, delivery robots, air taxis, high-speed trains, face-recognition payment systems, electric cars with fancy screens inside, skyscraper-building machines, and so on.

China’s lax regulatory climate — partly a result of cozy relations between local government and corporations, partly an intentional result of the central government’s high-tech push — has made the rollouts of these technologies faster and more widespread than in developed countries, where things like noise complaints and safety concerns predominate.

The electronics manufacturing boom (which actually predates the more recent high-tech push) has also resulted in a glut of cheap LEDs, which many Chinese developers have plastered all ov