July 2, 2025

This July 4th, I’m honoring two national anthems — one hopeful, one haunting

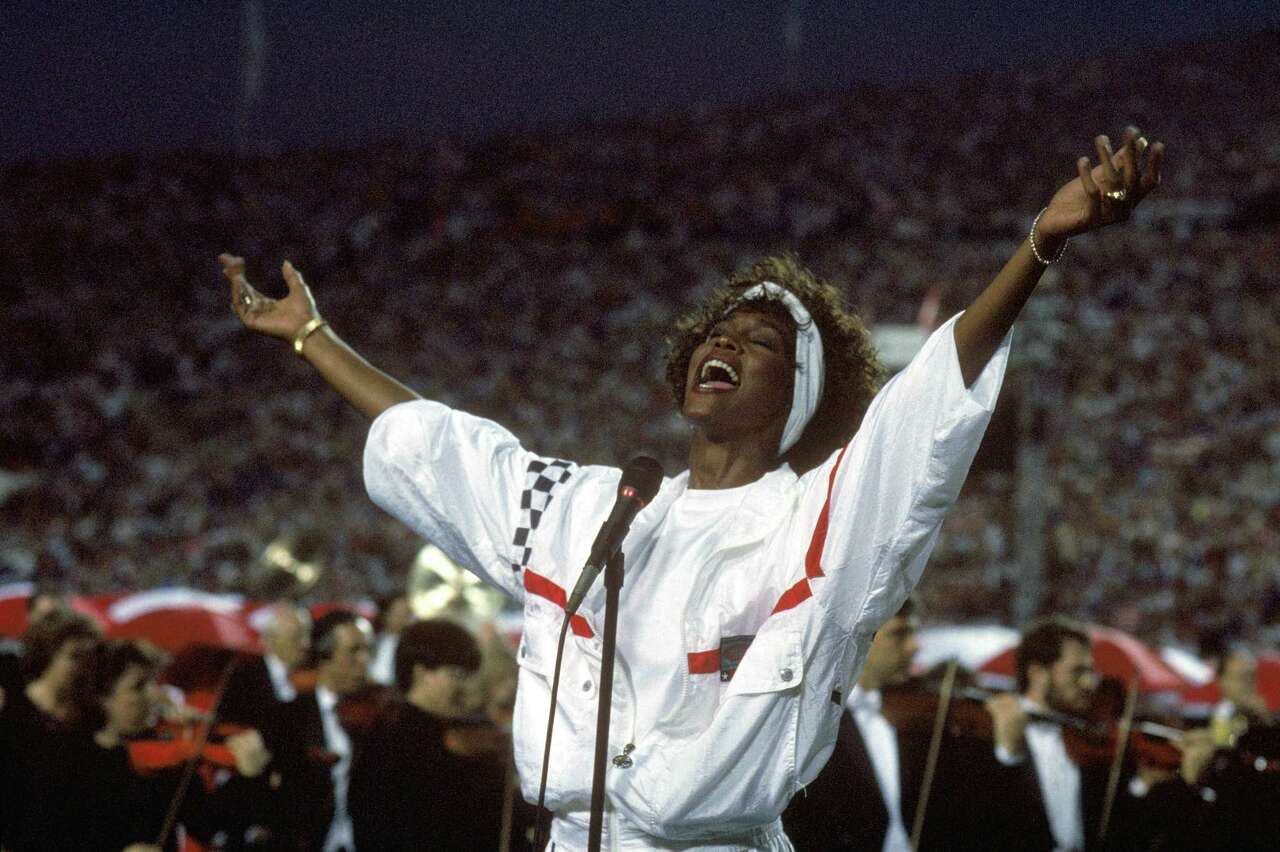

It’s that nonchalant tracksuit she wore, baggy as she pleased, smiling in front of an orchestra clad in cummerbunds. It’s that adorable headband pushing back her curls under the stadium lights. It’s her proud, glistening face and trembling lips as her voice belted, then crooned, then soared heavenly high before a flag-waving crowd of thousands — and millions more at home.

It’s all these things that leave me a puddle of patriotic tears at the end of Whitney Houston’s dazzling rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” performed in full-throated 4/4 time at Super Bowl halftime in 1991, months after the Persian Gulf War began.

It’s emotional, it’s exquisite, and, as her producer Rickey Minor later acknowledged, it was sung to a dead mic so that all the audience heard was her prerecording, albeit largely her first take in the studio.

I remember being disappointed upon learning that the 27-year-old Houston wasn’t doing her vocal magic on a tightrope quivering with the risks of live performance. Then I realized: that polished, well-orchestrated performance is what it is — an ideal, a symbol, an immaculate tribute. Kind of like that version of America we’re always striving toward.

The real America, especially these days with our discord and distrust, our families divided by politics, our universities under siege, our peaceful protests attended by the National Guard, our Home Depots the targets of ICE raids, is more like the national anthem performed by Jimi Hendrix.

Some critics have found his raging, wailing, grinding electric instrumental profane — the furthest thing from patriotic. I found it painful and unrelenting on my first listen. And that’s the point. This democratic experiment we celebrate every Fourth of July isn’t a pretty song.

Sometimes, it’s a mess, its melodies unrecognizable. Hendrix was willing to sing that song.

One rendition was immortalized at the mud-caked Woodstock festival in the summer of 1969, but Hendrix had been adapting different versions for at least a year, often mixing in a mournful staple from military funerals, “Taps.”

That Hendrix would shred America’s carefully guarded anthem so violently is even more impressive when you consider that just a year earlier, Puerto Rican-born singer José Feliciano was blackballed for performing his laid-back, folksy interpretation at the World Series, and a half century later, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick lost his career for merely taking a knee during the national anthem to protest racial oppression and police brutality.

Hendrix himself had been threatened when performing in Texas, according to musicologist Mark Clague, who wrote the 2022 book “O Say Can You Hear? A Cultural Biography of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Clague wrote in a 2014 essay that four months before Woodstock, Hendrix was playing at Sam Houston Coliseum in Houston when he began closing with his rendition of the “Star-Spangled Banner” and, according to his tour manager Ron Terry, “the cops got weird,” and one came over and pushed him up against a wall and told him to tell the band to stop. He managed to calm them and the song continued.

The next night, in Dallas, five men confronted Hendrix backstage, Clague wrote. Speaking only to Terry, who was white, they told him to tell Hendrix, whom they referred to by the N-word, that if he played the national anthem he wouldn’t “live to get out of the building.”

“No one does that in Dallas, Texas, and lives to tell about it,” Terry recalled one man saying. “We’ll start a riot, and if he don’t make it out of the building, that’s just the way it f------ goes.”

Hendrix played it anyway and made it out of the building.

A grainy video captures Hendrix at Woodstock on stage in a red headband and a white fringe jacket as he grinds out the first familiar chords of the anthem — vibrating with all their nostalgia and reverence and baggage.

The familiarity ends abruptly, as the line that would be sung “and the rockets’ red glare” erupts with a cacophonous mesh of screaming strings, percussive explosions, and the rapid gunfire of incessant strumming.

A timeless anthem

Hendrix’s guitar is not gently weeping – it is wailing for a nation mired in endless war and nearing the peak of anti-Vietnam protests.

For me, at least, there’s something mesmerizing and even cleansing in that noise, like a dissonant hymn bearing witness to America’s crises, both then and now. "This is America," Hendrix called his rendition, and how can we argue?

With only a few bars of solemn reprieve for “Taps,” Hendrix finally lets the piece resolve to a place of harmony. It’s not peace and justice and apple pies but perhaps a nod of affirmation that the American ideal is still possible.

“Hendrix’s Woodstock Banner is not a sonic destruction of flag or anthem,” writes Clague, professor of musicology at the University of Michigan. “Instead, it carries many patriotic trappings.”

He notes Hendrix’s own service in the Army’s 101st Airborne Division, and his solemnity as he plays, eschewing any trademark body tricks like picking strings with his teeth. He doesn’t purposefully play out of tune or insert comedic TV themes, as he had in other anthem renditions.

“Jimi Hendrix took stock of a nation in violent transition, making this process audible to his listeners as critique, as affirmation, and as call to action,” Clague writes.

I’m not comparing this moment now to the Vietnam era beset by military drafts and endless grieving. The sacrifices of those soldiers and their families are still being felt.

We have another battle raging today — one that threatens the core democratic freedoms our service members sign up to defend: free speech, academic freedoms, due process, the rule of law, civil rights. At stake is everything from right of transgender Americans to serve their country in uniform to the right of a U.S. citizen to walk to work and not be detained by her government because she looks Latina.

This year I will observe Independence Day knowing that the independence of many in this country is in jeopardy. I’ll wave the flag at the Fourth of July parade, stand for the veterans, marvel at the fireworks, and silently register my love for America with her hypocrisies and contradictions and transactional leaders.

I will mourn with Hendrix and dream with Houston. It's poetic in a way that some of the most brilliant interpretations of our national anthem, which was written by a slaveholder, have come from the descendants of the enslaved.

The songs of Houston and Hendrix are true — both the sacred and the profane. Will one prevail?

Our national anthem ends not with a statement but with a question: “O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave — o'er the land of the free and the home of the brave?”

Someday, I believe it truly will. Even when my faith falters, I remember: freedom is always singing, somewhere.

| Lisa Falkenberg, Senior Columnist - Texas |

What’s on your mind? What are y`ou curious or concerned about? Let me know by responding directly to this email or writing me at Lisa.Falkenberg@HoustonChronicle.com.

Unsubscribe | Manage Preferences

Houston Chronicle

4747 Southwest Freeway, Houston, TX 77027

© 2025 Hearst Newspapers, LLC