|

China has invented a whole new way to do innovation

Extreme vertical integration makes China's research system different than any other.

|

How did the screen you’re looking at right now get invented? There was a whole pipeline of innovation that started in the early 20th century. First, about a hundred years ago, a few weird European geniuses invented quantum mechanics, which lets us understand semiconductors. Then in the mid 20th century some Americans at Bell Labs invented the semiconductor. Some Japanese and American scientists at various corporate labs learned how to turn those into LEDs, LCDs, and thin-film transistors, which we use to make screens. Meanwhile, American chemists at Corning invented Gorilla Glass, a strong and flexible form of glass. Software engineers, mostly in America, created software that allowed screens to respond to touch in a predictable way. A host of other engineers and scientists — mostly in Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and the U.S. — did a bunch of incremental hardware improvements to make those screens brighter, higher-resolution, stronger, more responsive to touch, and so on. And voila — we get the screen you’re reading this post on.

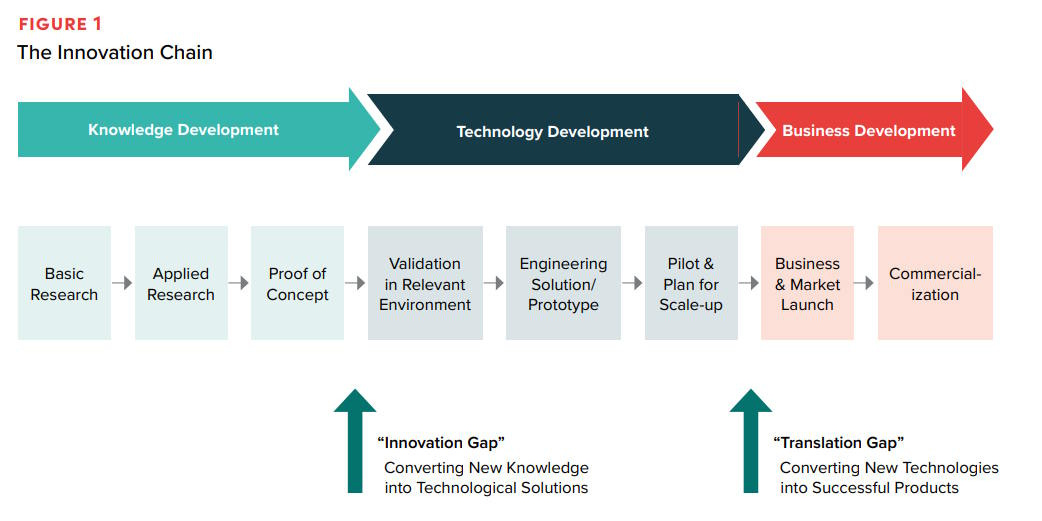

This story is very simplified and condensed, but it illustrates how innovation is a pipeline. We have names for pieces of this pipeline — “basic research”, “applied research”, “invention”, “innovation”, “commercialization”, and so on — but these are approximate, and it’s often hard to tell where one of these ends and another begins. What we do know about this pipeline is:

It tends to go from general ideas (quantum mechanics) to specific products (a modern phone or laptop screen).

The initial ideas rarely if ever can be sold for money, but at some point in the chain you start being able to sell things.

That switch from non-monetizable to monetizable typically means that the early parts of the chain are handled by inventors, universities, government labs, and occasionally a very big corporate lab, while the later parts of the chain are handled mostly by corporate labs and other corporate engineers.

Very rarely does a whole chain of innovation happen within a single country; usually there are multiple handoffs from country to country as the innovation goes from initial ideas to final products.

Here’s what I think is a pretty good diagram from Barry Naughton, which separates the pipeline into three parts:

|

Over the years, the pipeline has changed a lot. In the old days, a lot of the middle stages — the part where theory gets turned into some basic prototype invention — were done by lone inventors like Thomas Edison or Nikola Tesla. Later, corporate labs took over this function, bringing together a bunch of different scientists and lots of research funding. Recently, corporate labs do less basic research (though they’re still very important in some areas like AI and pharma), and venture-funded startups have moved in to fill some of that gap.

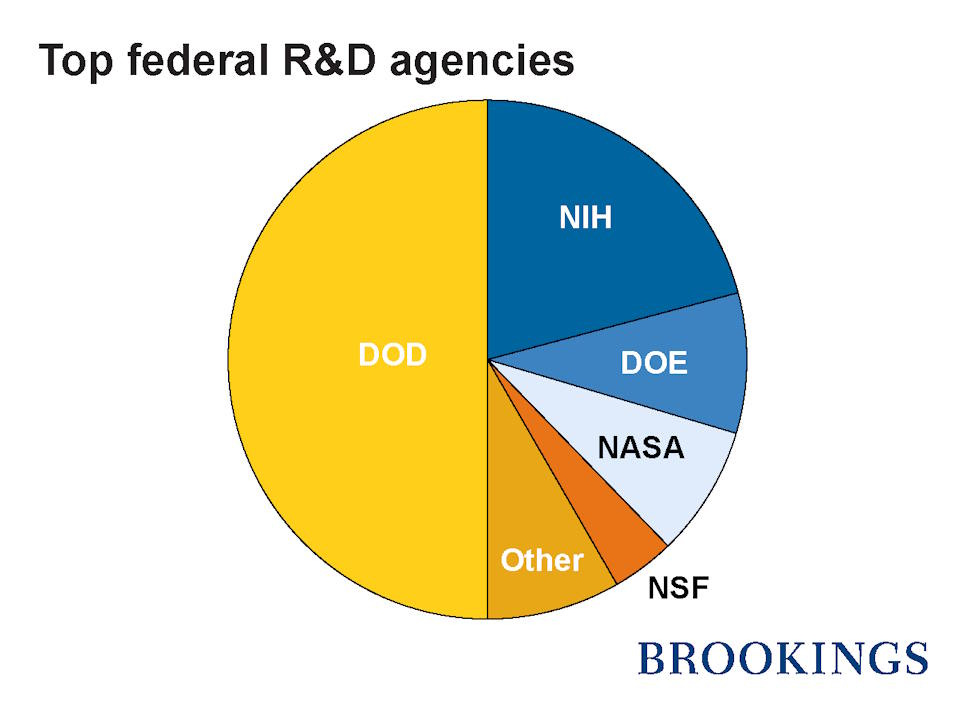

The early parts of the pipeline changed too — university labs scaled up and became better funded, government labs got added, and a few very big corporate labs like Bell Labs even did some basic science of their own. The key innovation here was Big Science — in World War 2, America began using government to fund the early stages of the innovation pipeline with truly massive amounts of money. Everyone knows about the NIH and the NSF, but the really huge player here is the Department of Defense:

|

Japan, meanwhile, worked on improving the later parts of the chain. I recommend the book We Were Burning for a good intro to the ways that Japanese corporate labs utilized their companies’ engineering-intensive manufacturing divisions to make a continuous stream of small improvements to the final products, as well as finding ways to scale up and reduce costs (kaizen).

And finally, the links between the pieces of the pipeline — the way that technology gets handed off from one institution to another at different stages of the chain — changed as well. America passed the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980, making it a lot easier for university labs to commercialize their work — which thus made it easy and often lucrative for corporations to fund research at universities. (This had its roots in earlier practices by U.S. and German universities.)

Meanwhile, in parallel, the U.S. pioneered a couple of other models. There was the DARPA model, where an independent program manager funded by the government coordinates researchers from across government, companies, and universities in order to produce a specific technology that then gets handed off to both companies and the military. And there are occasional “Manhattan projects”, where the government coordinates a bunch of actors to create a specific technological breakthrough, like building nuclear weapons, landing on the moon, or sequencing the human genome.

So we’ve seen a number of big changes in the innovation pipeline over the years. And different countries have done innovation differently, adding crucial pieces and making key changes as their innovation ecosystems developed The UK pioneered the patent-protected “lone inventor” model (with some forerunners of modern venture capital). Germany created corporate labs and the research university. America invented Big Science, modern VC, and DARPA, while also scaling up modern university-private collaboration and undertaking a few Manhattan-type projects. And Japan added continuous improvement and continuous innovation at the end of the chain.

That story more or less brings us up from the 1700s to the late 2010s. That’s when China enters the innovation story in a big way.

China’s innovation boom

Up through the mid-2010s, China had a pretty typical innovation system — the government would fund basic research, companies would have labs that would create products, and so on. China wasn’t really at the technological frontier yet, though, so this system didn’t really matter that much for Chinese technology — most of the advances came from overseas, via licensing, joint ventures, reverse engineering, or espionage. If you’ve ever heard people talk about how China &