|

|

Mesoscale News is one of Substack’s best-selling newsletters, with exclusive investigations, commentary, and breaking news, centered on climate, disasters and global politics. Consider upgrading to a paid subscription to continue supporting this work.

In this piece: we examine what defines a “mass shooting” in statistics, cover Australia’s gun law history, and discuss America’s ongoing gun violence epidemic.

With 391 mass shootings in the United States so far this year, there have been ample opportunities for Americans to debate necessary measures to curb gun violence.

Predictably, the conversation only seems to ignite when a school is targeted, a crowded public space is shattered, or an attack can be neatly packaged as political, ideological, or religious. The rest fade into the background noise of a country long accustomed to its own bloodshed.

This weekend, two separate attacks — one at Brown University, another at Bondi Beach in Australia — reignited that cycle. Almost immediately, social media filled with misleading claims and outright falsehoods about Australia’s gun laws and distorted comparisons to America’s rates of gun violence.

So before the outrage hardens into myth once again, let’s slow down and set the record straight.

Click here to read my post from Sunday examining the media coverage of both events.

What defines a “mass shooting”

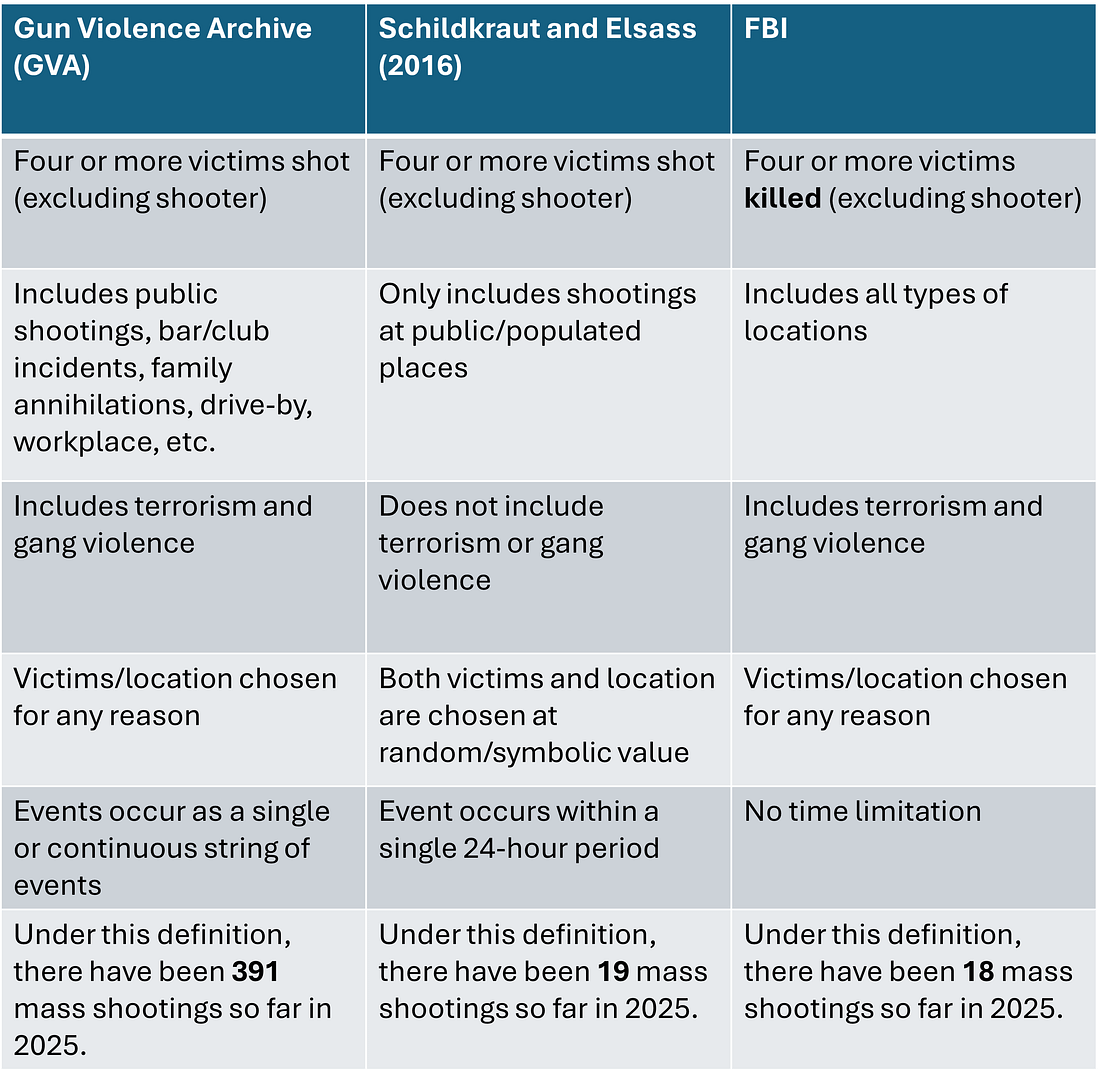

Before any serious comparison of gun laws across countries can begin, we have to do the unglamorous but essential work of defining our terms. The numbers people cite in these debates don’t simply exist — they are constructed, bounded by methodology, and shaped by what each dataset chooses to include or exclude.

“Mass shooting” is not a single, universally agreed-upon concept. It’s an umbrella term covering several distinct statistical definitions, each designed for a different analytical purpose. What they share is one critical constant: none of them include the shooter or shooters in the casualty count. Only victims — those injured or killed — are counted.

Gun Violence Archive (GVA) Definition

In the United States, the most commonly referenced definition comes from the Gun Violence Archive (GVA). Under the GVA framework, a mass shooting is any incident in which four or more people are shot, whether injured or killed, excluding the shooter(s).

This definition is intentionally broad. It captures the full scope of firearm violence in public and private spaces alike, from schools and workplaces to apartment complexes and neighborhood gatherings. Its purpose is not to isolate motive, but to measure frequency and harm.

FBI Definition

The FBI uses a far narrower lens. Within its “mass murder” classification, the threshold is four or more people killed, not merely injured, again excluding the shooter(s).

This definition dramatically reduces the number of incidents counted, because it omits shootings where victims survive — even when those events involve the same level of chaos, terror, and public risk. As a result, FBI statistics are often more conservative but also less representative of how gun violence is experienced by communities.

For example, the shooting at Brown University would not be counted in FBI data because while 11 people were shot at a public place, only two died.

Schildkraut and H. Jaymi Elsass (2016) Definition

Then there is the most restrictive definition, developed by Jaclyn Schildkraut and H. Jaymi Elsass (2016) and commonly used in academic research. Their criteria require four or more victims shot (injured or killed) in a public or populated location, within a single 24-hour period, where victims are selected randomly or for symbolic or personal reasons.

Crucially, this definition explicitly excludes gang-related violence, domestic violence, and terrorism-linked attacks. The goal here is analytical precision — isolating a specific phenomenon of public mass violence — not capturing the full toll of gunfire.

Each definition answers a different question. The problem arises when they are mixed interchangeably, or worse, weaponized to minimize reality. Narrow definitions produce smaller numbers that can feel reassuring. Broader definitions reveal the scale of violence most Americans actually live with.

So when we compare gun violence across countries — or argue about whether a problem is “rare” or “overstated” — the first and most honest step is to ask: Which definition are we using, and why?

Because statistics don’t just measure reality. They frame it. And in a debate this consequential, framing is everything.