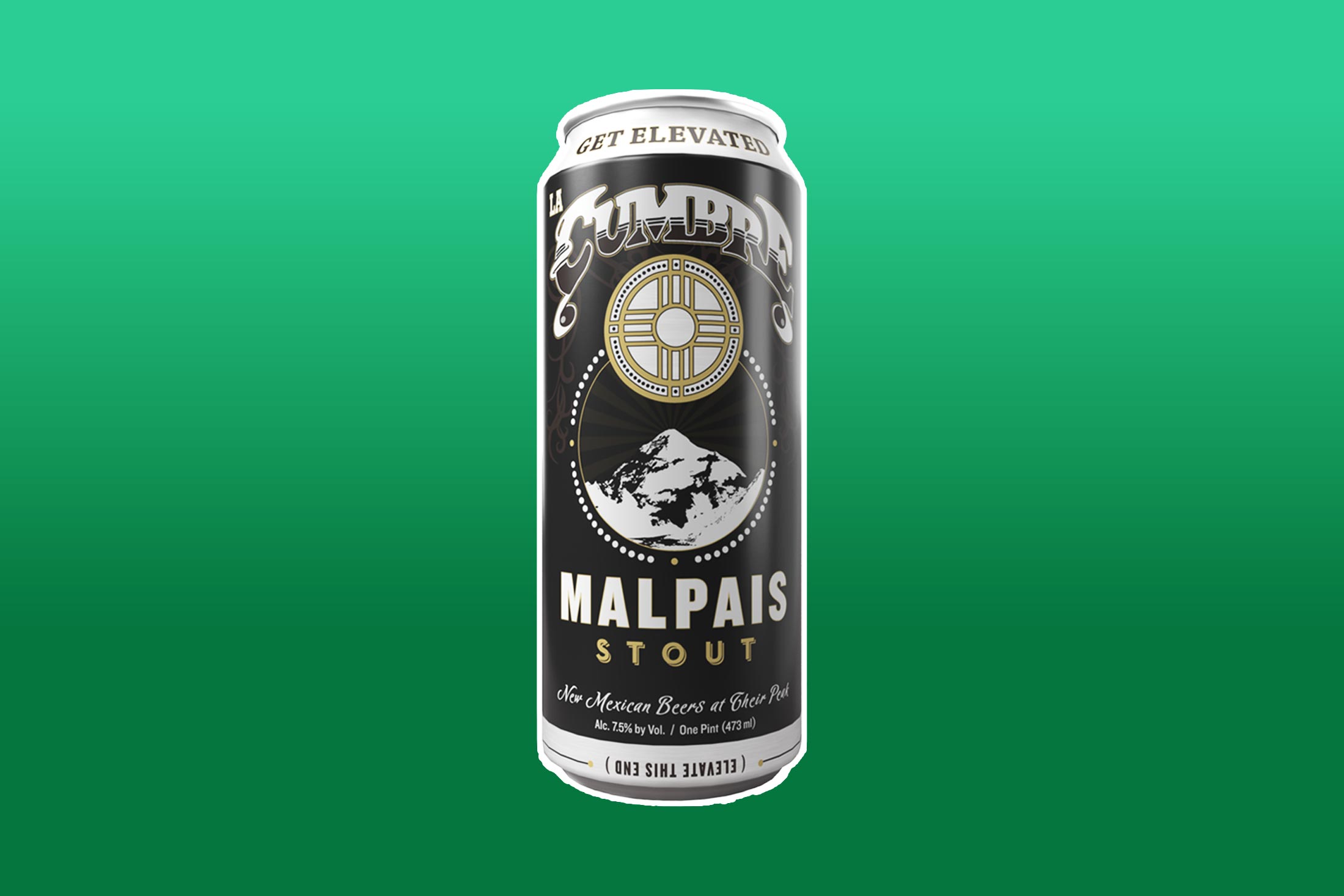

| Every March 17 a dear friend of mine, a publican with strong roots in the Emerald Isle, is fond of saying, “The Irish don’t drink green beer, they drink dark beer.” He’s referring, of course, to Guinness, the iconic black (actually, dark red) stout with the dreamy, creamy head of foam straight from Dublin. Drinkers around the globe down about 13 million pints of the stuff every St. Paddy’s Day (819% more than any other day of the year)—and I proudly pull my weight. But ever your intrepid tap-list explorer, if I’m sitting down for a daylong merriment marathon, I’m going to want to branch out on my stouts. Guinness might be Ireland’s best-known, top-selling beer, but it doesn’t have a monopoly. Other excellent import stouts include Beamish (a tad sweeter than Guinness, but with a similar, luxuriant mouthfeel); Murphy’s (heavier and roastier); and O’Hara’s (slightly bitter with a faint coffee finish). On a day when everyone gets to be honorarily Irish, though, why not go on the lash with something local? Many smaller craft breweries and brewpubs in the US work up something dark and special for the holiday, in addition to their already great year-round stouts whose range belies the style’s more or less monochromatic appearance. There’s an entire spectrum of expressions, ingredients and flavors within the category. In compiling our St. Pat’s stout primer, I turned to the expert palate of Annie Johnson, a beer columnist and Irish dual citizen who won the American Homebrewers Association’s 2013 Homebrewer of the Year. Her first piece of advice on American-made dark beers: Beware. “We Americans make our porters and our stouts the way we drive our trucks: bigger, louder, more expressive,” Johnson says. That exuberance usually translates to the American alcohol content as well. “In Ireland you’re there to celebrate and enjoy the beer over time. To meet, to talk. Here we don’t do that.”  Johnson at the Guinness Storehouse Gravity Bar in Dublin. Source: Annie Johnson So if you want to emulate the Irish on their special day—or just make it through the day and into work the next morning—Johnson recommends paying attention to the potency of your dark pint. Guinness, for reference, weighs in at a deceptively lean 4.2% alcohol by volume, the same as Bud Light. That means you’ll want to steer clear of anything barrel-aged that will often register in the double digits of ABV. Likewise, a Russian imperial stout (“imperial” in beer generally means “big” or “more” of everything from flavor to booze) will tip you into tipsy with its average 8% to 12% ABV. “Besides,” says Johnson, “it has nothing to do with Ireland.” And leave those decadent pastry stouts—made from fudge, pie, cake, doughnuts and all manner of confection—where they belong, as liquid dessert. That leaves us with five quaffable styles of stout you’re likely to have handy this St. Patrick’s Day. Note: Some styles may cross over, as in coffee in a milk stout or oatmeal and coffee in a breakfast stout. Dry Irish StoutThis style is characterized by roasted malts, which give the beer both its dark appearance and its warm, rich flavor and dry, slightly bitter finish. You’ll often see it served “on nitro,” meaning it’s infused with nitrogen instead of carbon dioxide to give it a creamier mouthfeel. “When they tell you they have a dry Irish stout, they’re trying to mimic Guinness,” Johnson says. Foreign Extra Stout  Malpais Stout (7.5% ABV) from La Cumbre Brewing Co. in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Source: Vendor It’s a rarer find in craft circles, but it’s still good to be able to spot this one. Foreign extra stout is essentially a slightly bigger malt-forward version: bigger in alcohol and flavor, including tropical notes. Oatmeal Stout  Oatmeal Stout (5.7% ABV) from Schlafly Beer in St. Louis. Source: Vendor It has a great balance among malty, sweet and still roasty, and the oats also give this style a distinctive smooth, rich body and mouthfeel. (Be careful asking for this in any hardcore Hibernian establishment: It’s a British style.) Coffee StoutThere might be some of this typical winter release left. Brewers “warm” their brew with coffee to augment the already roasty malts and give the beer the aroma and bitterness—hopefully without the acidity—of a cup of joe. Varieties of coffee beans also give beermakers the ability to riff on all sorts of coffee notes, from toffee to chocolate to vanilla. Milk StoutNow we’re veering into the sweeter stuff. But there are still plenty of milk stouts, also known as cream stouts, that have the velvetiness, richness and slight sugar of added lactose without giving you a cavity or tummy ache. Johnson reminds us that the Irish also love their lagers (particularly Harp), red ales (Smithwick’s and Kilkenny), and ciders (Magners), and whiskey, of course. As for drinking green beer? “I’m not a beer snob,” she says. “If you want to have green beer, go ahead. But you might bring your own food coloring—a lot of bars tend to add too much, and it’ll stain your teeth.”  If you’re really looking to celebrate, Bushmills 46 is the oldest Irish single malt to date—and Brad, our Top Shelf whiskey expert, got an exclusive first taste. Source: Bushmills 46 What beer first made you go wow? Have a tale of discovering a whiskey or cocktail that’s become a lifelong favorite? Is there a wine you can’t stop talking about? Email us at topshelf@bloomberg.net, and you might be featured in a coming Top Shelf newsletter. Last summer, I was at Riggs Beer Co., a brewery on a small family farm in Urbana, Illinois. I was there to check out the American lager, which I’d heard was about as close to a true, pre-Prohibition domestic lager as you can find these days (read more about that in my 2024 Best Beers list). I bellied up to the small bar alongside three older gentlemen wearing jeans or denim overalls, as if they’d just come out of the fields to cap the workday with a cold one and some camaraderie. When, without a word, the bartender brought each of them not that lager, but a tall, shapely glass of golden hefeweizen. I was taken aback. Hefeweizen is a German-style wheat beer (the term is a combo of the German words for “yeast” and “wheat”) that’s unfiltered, so it pours cloudy with suspended wheat and yeast proteins—it’s the original hazy! And it was a staple on almost every brewpub’s board of fare in the early days of independent brewing, as an ideal gateway beer: something as light and unoffending as a macro lager, but still flavorful.  Okay! hefeweizen at Blue Jay Brewing Co. in St. Louis. Ain’t she a beaut? Photographer: Tony Rehagen Instead of the hops overwhelming the palate, the yeast drives the flavor, creating subtle (and not so subtle) spice and fruit notes of clove, bubblegum and the hefe’s signature taste: banana. In fact, it was that cloying banana characteristic, and brewers getting a little carried away with it, that initially drove me away from the style in favor of hoppier IPAs and crisper lagers. Now the style seems to be experiencing something of a renaissance, and not just in Southern Illinois. Modern brewers have reined in the banana and clove to put new spins on the old hefe. For instance, a flagship of St. Louis’ Blue Jay Brewing Co., the Okay! hefeweizen is more banana bread than just fruit, with a strong but not intrusive hop character to keep it sharp and refreshing. Bonus: A well-poured hefeweizen is one of the most beautiful beers to behold, served bright, straw-and-orange-tinged, in a tall vase-shaped glass of the same name. It’s liquid sunshine as the weather heats back up. Prost! |