- An S&P 500 correction + $3,000/ounce gold = A very big shift away from risk.

- What, me worry? The proposed US sovereign wealth fund looks a vital tool for Bessent.

- One key question: Where will the money come from? Land sales?

- Germany’s big deal to expand fiscal policy is still on track — more analysis later in the week.

- Central banks are giving themselves increasing leeway in inflation targeting. For how much longer?

- AND: Songs to commemorate financial landmarks, from 666 to 1999.

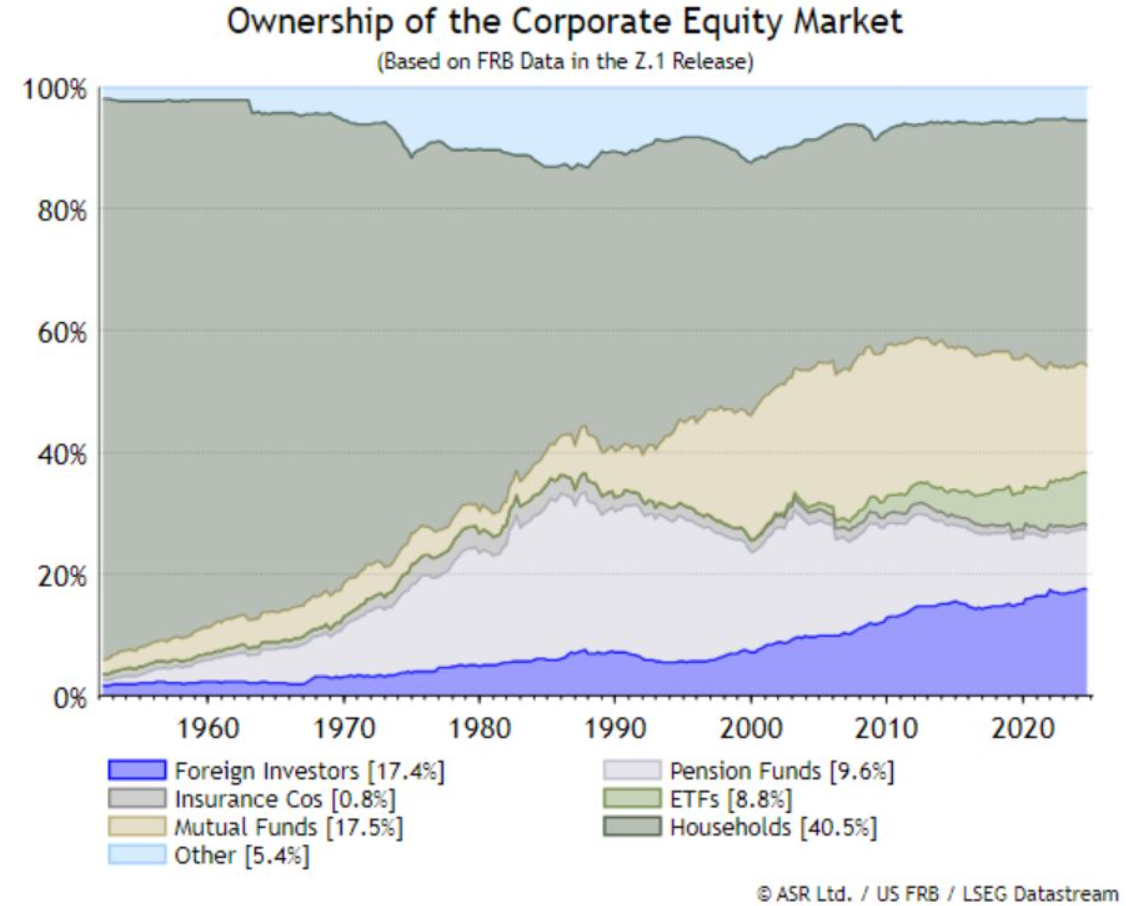

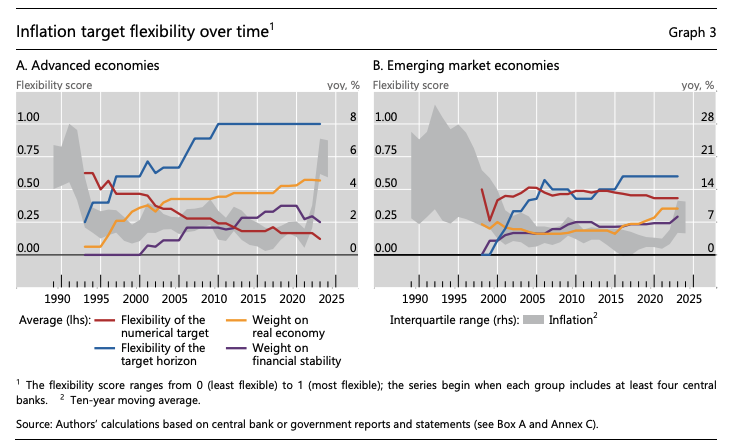

Corrections and Sovereign Wealth Funds | Scott Bessent says he isn’t worried. In the last week, market overconfidence has been replaced by a drastic dose of nerves. When the S&P 500 drops by more than 10% from its peak, and gold passes a big landmark ($3,000 per ounce), then the perception of risks has changed radically. This is how gold and the S&P have performed since 2020: That new awareness of risk has come at the same time as a startling grasp that other countries’ stock markets might just offer a good alternative to the US: Speaking on NBC, Bessent made clear that he could live with market corrections, which can often be healthy. He’s clearly playing a long game (even if the administration’s more erratic shifts in position on tariffs tend to obscure this). The US is backing away from globalization, as is plainly the wish of voters. But the world system of the last 80 years has offered some big advantages to the US, including downward pressure on inflation (from untariffed imports) and lower interest rates, and higher asset prices (as foreigners recycle their trade profits by buying US bonds and stocks). A stock market correction from a high level isn’t much of a price to pay if the US can indeed find its way to a more self-sufficient (or “autarkic” in the economic jargon) system that retains most of these benefits. And that, I increasingly grasp, will depend on the proposal to set up a US sovereign wealth fund. Here are the main points: It’s Not as Far-fetched as It Seems The biggest and most famous SWFs (like those of Norway or Saudi Arabia) take revenues generated by exports — generally from oil or other resources — and diversify them. America’s problem is that it has a trade deficit, not a surplus. It lacks a big supply of export receipts to recycle into anything. However, roughly half of SWFs aren’t based on such revenues, according to the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds, and the US has other potential sources of capital. Exciting options that have been canvassed include revaluing US gold reserves to their current market price and putting the massive paper profit to work in an SWF, or funding it with seized cryptocurrency. But Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research suggests that it should be easier. The government owns a lot of land, valued 10 years ago at $1.8 trillion, and presumably worth far more now. It also owns a range of nationalized industries, from the Tennessee Valley Authority to Amtrak. Selling land or companies, at a discount to fair value to make sure there were buyers, would fund a SWF quite nicely. The UK’s radical privatization program under Margaret Thatcher provides a template. It’s also not as much of a political challenge as first appears, since the Democrats under President Biden had already been exploring just such an idea. So while it can sound rather overblown, it’s far more feasible than many of the other policy actions that have been batted around. It Could Be a Necessary Piece of the Trumpistas’ New System The flip side of the trade deficit is that other countries are left with huge holdings of US assets. Freedom of capital flows has boosted demand, particularly for Treasuries (seen as risk-free) and Magnificent Seven stocks (which are now treated as though they’re almost risk-free). If countries are selling less stuff to the US because of tariffs, they will have less money to park in US assets — and may also want to take the money home in any case. The ownership of the US stock market shows the growing importance of foreign buyers:  Source: Absolute Strategy Research A more autarkic world in which goods flow less freely will almost certainly mean that capital also flows less freely. The former would be good for the US. The latter, on the face of it, would be bad. This is the gaping flaw in the plan to restructure the world trading system — and whether the creation of a big, patient buyer funded by monetizing US natural resources might fill that gap and take over the role of foreign finance. How It Will Actually Work Is a Huge Question Sovereign wealth funds fall into two broad categories. Singapore’s pair are handy exemplars: GIC behaves like a massive macro hedge fund, trading in different asset classes around the world, while Temasek is more like a conglomerate, taking large active stakes in a few companies. GIC’s declared purpose is to manage Singapore’s reserves, while Temasek calls itself “a generational investor which seeks to do things today with tomorrow in mind.” Think of GIC as a Millennium, and Temasek as more of a Berkshire Hathaway. There are arguments for both, if done well. Trump appeared to have more of a Temasek model in mind when he called for a fund “to finance great national endeavors.” But that is up for grabs. Torsten Slok of Apollo Management offers this handy schema of what Bessent and his colleagues are trying to engineer. He suggests that the need is for an entity that can behave like GIC, buying and selling currency reserves to ensure that the dollar doesn’t strengthen too much: Yes, Plenty Could Possibly Go Wrong It can be difficult to stop a large government-owned fund from slipping into an attempt to “pick winners.” British Leyland, the huge and ungainly nationalized roll-up of British carmakers in the 1970s, offers a painful memory. An American SWF that went about funding new steel mills or auto plants might fall victim to the same problem. There’s also a risk of more conscious malfeasance. Politicians mustn’t be able to use such a fund as a handy wallet to make useful transactions. The US SWF has been proposed as a place to hold TikTok if its Chinese owners are eventually forced to sell, or to park a crypto reserve. Both might be viewed as the start of a very slippery slope. The transparency and corporate governance of any such entity will be vital to maintain the necessary trust. And then there are the left-wing and environmentalist critiques, which do have some merit. The complaint about Thatcher was that she was “selling the family silver,” and that assets that previously belonged to everyone had been sold to a few for less than they were worth. Selling land in the American West brings obvious risks to the environment, and to the nation’s natural heritage. Bessent and Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick are due to report on how their SWF might work in May. Although below the radar for now, this is one of the biggest and most complicated decisions the Trump team will have to make. The next meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee is due Wednesday, but there’s a degree of assurance of its final decision. Virtually nobody sees any chance that interest rates will move, and the market has steadily converged on this view for some months: This confidence is primarily inspired by the committee’s pivot to transparency in monetary policy since the early 1990s. The Fed adopted a form of inflation target in the middle of that decade, but it wasn’t publicly disclosed until 2012 after the Great Financial Crisis. It took numerous tweaks, such as the addition of the maximum employment mandate, before the landmark announcement under Ben Bernanke. It’s hard to make a case against transparency as far as business decision-making processes are concerned. But exactly how inflation targets are supposed to work is tricky. This International Monetary Fund article does a better job of chronicling the journey of the framework since New Zealand first adopted it 35 years ago. Some central banks target a numerical point, others a range. Their horizon to achieve them varies. The question is about the framework’s constraints, whether it’s too restrictive or loose to attain price stability, and whether it’s consistent with other targets of employment and financial stability. This was the focus of recent research by the Bank for International Settlements of targets at 26 central banks. Claudio Borio and Matthieu Chavaz concluded that other objectives are starting to matter more than price stability: Under the surface, such frameworks’ flexibility has evolved significantly. On the one hand, the explicit weight on objectives other than inflation — real economy objectives such as output and employment and, to a lesser extent, financial stability — has grown. On the other hand, the pursuit of those objectives has been facilitated through greater flexibility of the horizon over which the target is to be achieved, even as the target itself has become less flexible.

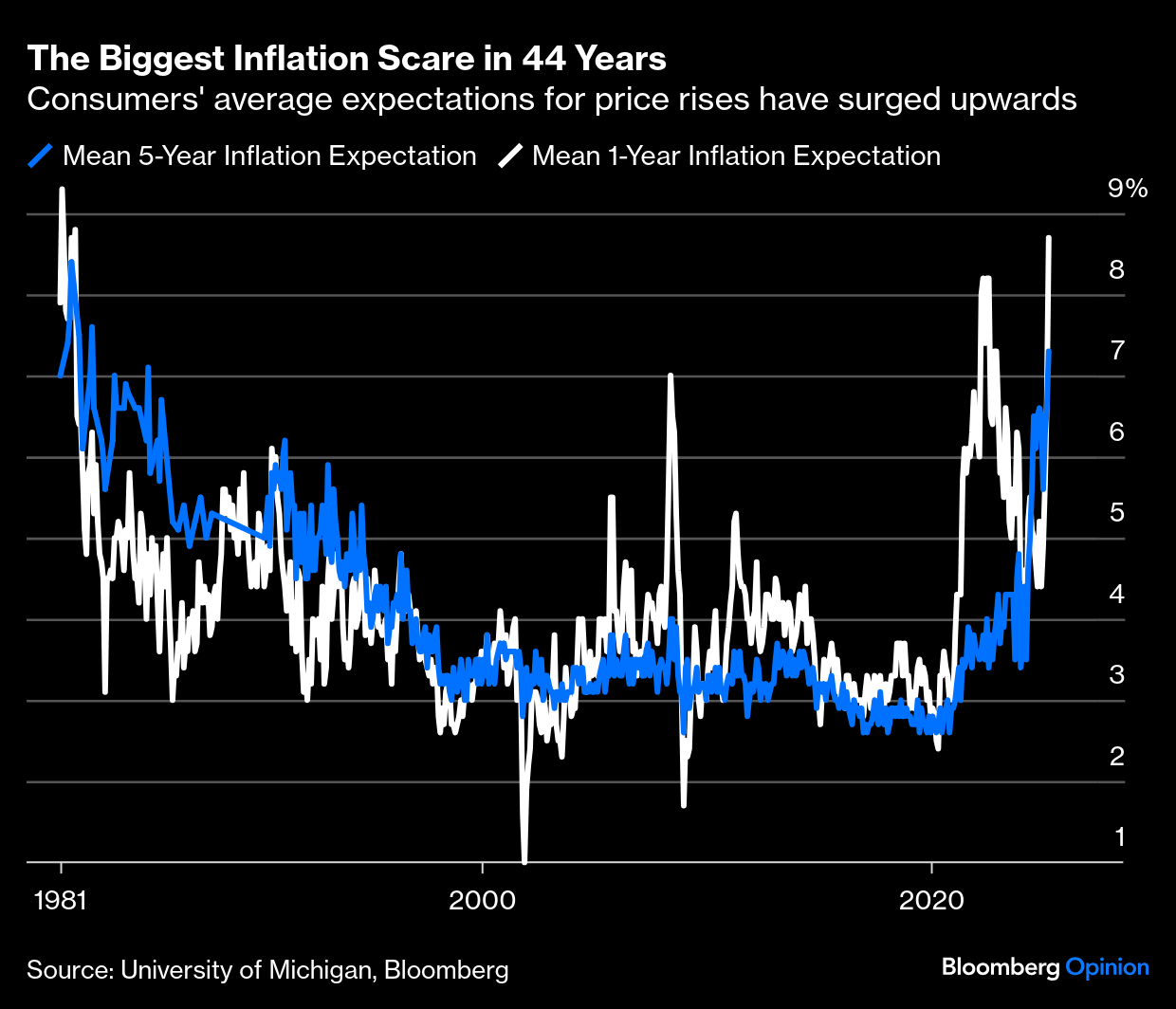

Put differently, central banks are giving themselves more wiggle room. Flexibility means simply the degree to which the framework tolerates fluctuations in headline inflation and allows the pursuit of other objectives. The BIS quantified this. As more central banks adopted stricter numerical-points inflation targets (shown in the red line in the chart below), they gave themselves far more time to achieve them (in blue), granting themselves the opportunity to do other things:  Source: Bank of International Settlements The angst about tariffs, which has come when the effects of post-pandemic inflation were only just beginning to settle, could make it harder for central banks to make their targets more flexible. The latest survey of US consumers by the University of Michigan shows that mean inflation expectations are their highest since 1981:  Expectations like that would normally require an inflation-targeting central bank to ratchet up rates. So even if its course for this week is clear, the Fed faces some difficult decisions. In May, it will host a conference as part of a regular review of monetary policy strategy. It’s focused on the FOMC’s Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy — which in 2020 switched to targeting an average for inflation rather than a fixed level — and its communications tools. The 2% longer-run inflation goal is under consideration, and indeed may no longer be realistic. But with inflation expectations coming unanchored for the first time in a generation, this could be a dangerous time to admit to being flexible. —Richard Abbey A last installment of songs that are recurringly useful when needing to liven up some dry discussions of markets: The Number of the Beast by Iron Maiden (the S&P 500 bottomed at 666 after the Global Financial Crisis); Stop, Stop, Stop by The Hollies; What the Hell Just Happened? (frequently the most honest headline available) by Remember Monday; Turning Japanese by The Vapors, Oscillate Wildly by The Smiths; Black Monday by Sleaford Mods; FOMO by Jordan Sandhu; The Wall Street Shuffle by 10cc; and Maria Bartiromo by Joey Ramone (it’s an ode to her when she was the goddess of CNBC rather than an opinionator on Fox Business). Have a great week everyone.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Marc Champion: The Ukraine Ceasefire Will Test US Intentions Most of All

- Max Hastings: The US Has Turned Its Back on Its Past. Now What?

- Marcus Ashworth: The Transatlantic Bond Shock Has Room to Run

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |