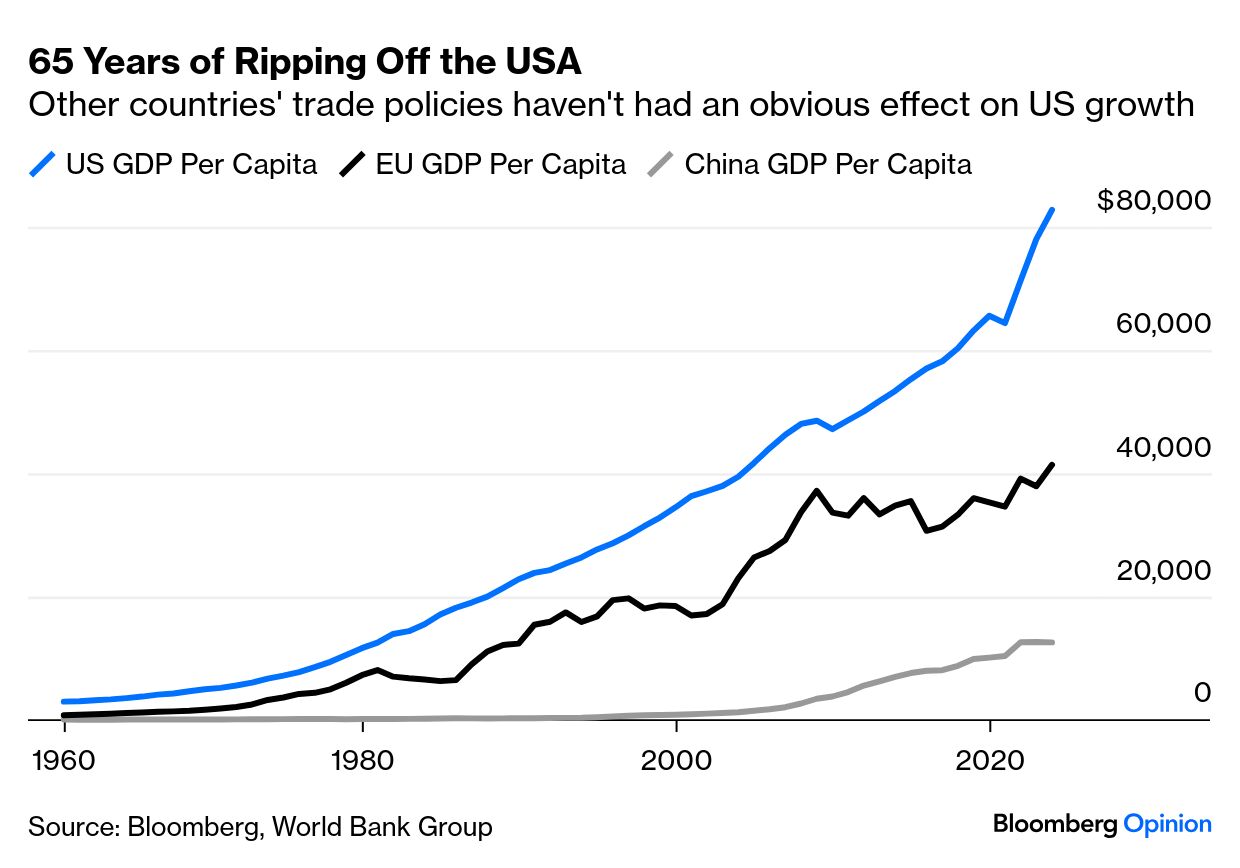

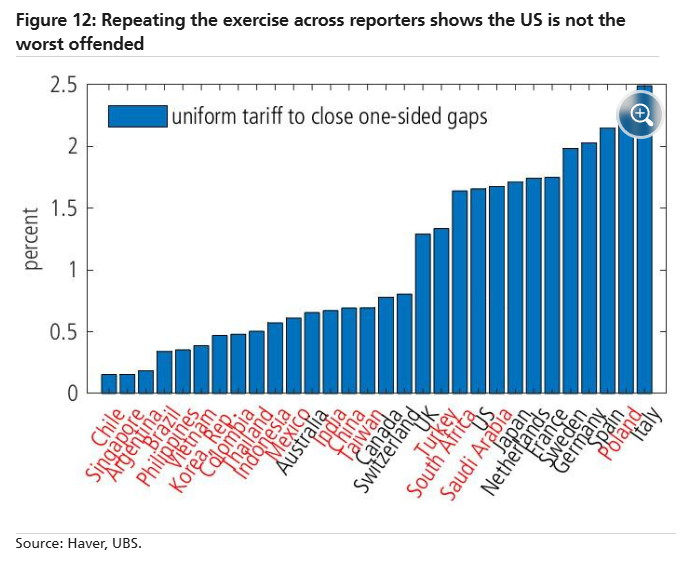

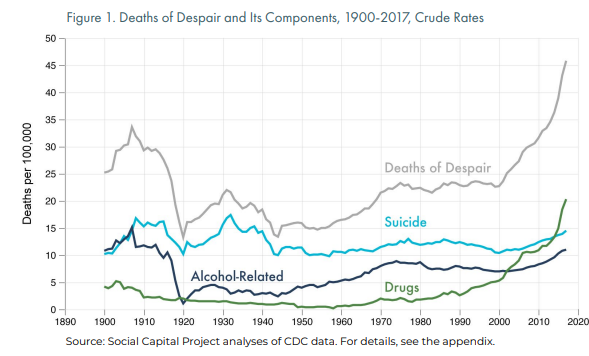

| Why is the US complaining of being victimized for 70 years when in reality, it’s ruled the world and enjoyed great prosperity? This might be the greatest mystery of all. In absolute terms, nothing bad has happened to the US economy over the last few decades. Its gross domestic product per capita is much greater than that of the European Union or China, and continues to grow healthily. If the US is being taken advantage of, it doesn’t show up in the aggregate figures:  When it comes to trade barriers, it’s also hard to see why the US feels aggrieved. It has led a steady opening of the world to trade for decades, sparking passionate opposition from the left, who think the terms overly favor America and that smaller countries are entitled to protect their economies more. The GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) begat the World Trade Organization, all after drawn-out negotiation and much protest. Yet Karoline Leavitt, the president’s press secretary, denied that the Liberation Day tariffs were part of a new negotiation: “These countries around the world have had 70 years to do the right thing by the American people, and they have chosen not to.” Apparently, none of the postwar trade negotiations count for anything. It’s bizarre that anyone could even think that. One more way to measure this: Arend Kapteyn’s team of economists at UBS analyzed what effect truly reciprocal tariffs (in which each country charges the same tariff on each product as it is charged by its trading partner, product by product and country by country) would have on overall levies. The chart shows how much each country would have to raise overall tariff rates to get to a point of true reciprocity with all its partners. The more it needs to raise them, the worse deal it’s receiving.  This data-crunching was a waste of time because the US isn’t interested in truly reciprocal tariffs. But it does reveal that the US would need to raise its total levies by only about 1.5% to get to the point where nobody was ripping it off. For most emerging nations, this number is much lower, meaning that they generally impose higher barriers. But 1) 1.5% isn’t a massive rip-off and 2) the exercise shows that Saudi Arabia, Japan, and most of the bigger EU economies are getting ripped off by more. For one last example, the North American Free Trade Agreement with Mexico and Canada is cited as a particular grievance that inflicted harm on the US. But the great sucking sound from south of the border hasn’t helped Mexico. In the 1960s, it was a far wealthier country than South Korea. Nafta didn’t help it regain that status, even though it now enjoys far better trading terms with the world’s largest economy. So where does this idea come from? The problem isn’t the size of America’s economic pie, or its portion of the global pie, but the way it’s shared between Americans. Globalization has had a grievous effect on US manufacturing jobs that has stoked inequality. This isn’t populist myth-making; it’s been a five-alarm fire for economists, politicians, and Main Street for well over a decade. Most notoriously, Angus Deaton and Anne Case coined the term “deaths of despair” to diagnose an acute social crisis:  Source: Social Capital Project, US Senate This isn’t going away. The Atlanta Fed publishes data for how wage growth varies across the income spectrum. The lowest paid, in the first quartile, tend to get higher percentage increases; they start from a lower base and it’s cheaper to give them a raise. But for long periods under George W. Bush and Barack Obama, the fourth quartile actually received better percentage raises. Disconcertingly, the pandemic’s brief Robin Hood effect is over, hikes for the lower paid are dwindling, and the pay gap is widening again: This is why a large chunk of the US population can be convinced that the rest of the world has ripped them off. Deindustrialization and rising inequality wouldn’t have happened without globalization. But it wasn’t a sufficient condition for everything that happened. The US economy grew throughout, yet nobody found a way to redeploy the people impoverished by globalization. That wasn’t inevitable, and can’t be fixed by blocking off imports. The government might have intervened to stop inequality reaching this point, most logically with the traditional left-wing remedy of redistributive taxation.

That’s a complete no-no in contemporary US political culture, and I’m not recommending it. But it’s far more logical than announcing a virtual trade embargo on others to retaliate against an imaginary rip-off. Why is the dollar falling, even though Treasury yields are rising?

Usually, the bond differential is a crucial currency driver. Money flows where it can get the higher yield. Except recently. In early Asia trading, the DXY dollar index dropped to a three-year low: After US Vice President JD Vance launched his attack on Europe two months ago, Day, prompting a desperate European attempts to beef up their defense, the spread of German over US yields ballooned but then came straight back down. Meanwhile, the euro has surged upward. If you’re reading this on the terminal, try opening this chart in GP so that you can look at it on two scales overlaid, which will make the divergence even clearer: A further weirdness post-Vance: Germany is now going to borrow far more, which should make its bonds less attractive. The US is taking a chainsaw to the federal budget in a brutal attempt to cut the deficit and borrow less. But the prices of bunds and Treasuries, as measured via exchange-traded funds tracking them, show that Germany has gained while the US has dropped. This is stunning: It’s true that US yields still aren’t all that high. At Friday’s close, the 10-year yielded just under 4.5%; it hit 4.8% in January, and briefly topped 5% in 2023. But the speed demands attention — it gained 50 basis points last week. The last time that happened was in November 2001: Another problem: The week’s price action tends to confirm that bond yields are in a rising trend that started five years ago. Such things matter in the bond market, which tends to follow long cycles: Put all these together, and the only explanation is a loss of confidence in the US as a destination for funds. Last week's combination of rising yields and a falling currency is reminiscent of any number of emerging markets crises, and of the one for gilts and sterling that followed Prime Minister Liz Truss’s unfunded UK tax cuts in 2022. It’s amazing that such a fate can befall the US. Truss capitulated and sterling rebounded; that’s generally the pattern that emerging crises follow. Amazingly, that is now the template for the US. Why is the US making concessions to China, when it appears that Beijing has far more to lose? Trade is more important to China than to America, and its economy is in a more dubious place at present. But game theory (and common sense) show that what matters most when dealing with an aggressive bully is pain threshold. If you can soak up more pain than they can, you’ll prevail, even if it hurts. Trump owes his election in large part to popular anger over inflation that peaked at less than 10%. In China, the Communist Party killed millions during the Cultural Revolution; set tanks on peaceful protesters in Tiananmen Square; and only three years ago imposed Covid lockdowns far more draconian than anyone else, which by then were clearly excessive. China’s leadership evidently has a far higher threshold for the pain it will inflict on the population before conceding. It also has a much more prevalent myth of mistreatment by the rest of the world, reinforced by Vance’s extraordinarily offensive soundbite that the US was buying products made by Chinese peasants. Xi Jinping has far greater control over his media than Trump. Additionally, the US position is weaker than it appears. Much of its Treasury debt is in foreign (particularly Chinese) hands. The stock market is worth more than all the others put together, even though its economy is only about a quarter of global GDP. This is a recent development, and means that the US has much more to lose from capital flows — which can adjust far more quickly than trade flows: Also, steady global economic growth increases potential trade with other countries. Yes, a trade war with the US would hurt, but there are alternatives: The US has more to lose than anyone else, because it starts with more. That’s why it shouldn’t be surprising that China is retaliating while calling the US policy a “joke.” What’s up with these China tariffs? Are they on, off, delayed? How is anyone supposed to make sense of this? OK, this question doesn’t fit the Passover format, but it’s on everyone’s lips. Thursday brought confirmation of a 145% US tariff on all Chinese imports from the US. Friday came the announcement that laptops and phones (the most significant of those imports) were to be excluded. And then on Sunday morning talk shows, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said that reprieve was only temporary, and the president said he would look at “the whole electronics supply chain.” The most important message is that the administration grasps that there are limits on how much pain it can inflict on the business models of Apple Inc. and Nvidia Corp., which each were recently worth more than $3 trillion. In the last three months, their joint value dropped by a third, or more than $2.5 trillion: It’s been popular of late to argue that the administration can happily let the stock market fall, as many Americans aren’t exposed to it. But the people who fund Trump tend to be rich, and they’re grievously hurt by this. If last week’s step back acknowledged that he couldn’t stare down the bond market, the weekend moves on electronics also suggest a Trump Put at which point he’ll intervene to help out stocks. The bottom line for markets: The US is in a weak place and making concessions. That’s good news compared to the last couple of weeks, so an equity rally at Monday’s open seems likely. That said, the sheer ad hoc nature of policymaking over a sector as important as iPhones and laptops shows ever more conclusively that the children are in charge. This is amateur hour, and terrifying. Ultimately, nobody can give a confident answer to the fourth question. Risks and volatility are likely to continue. |