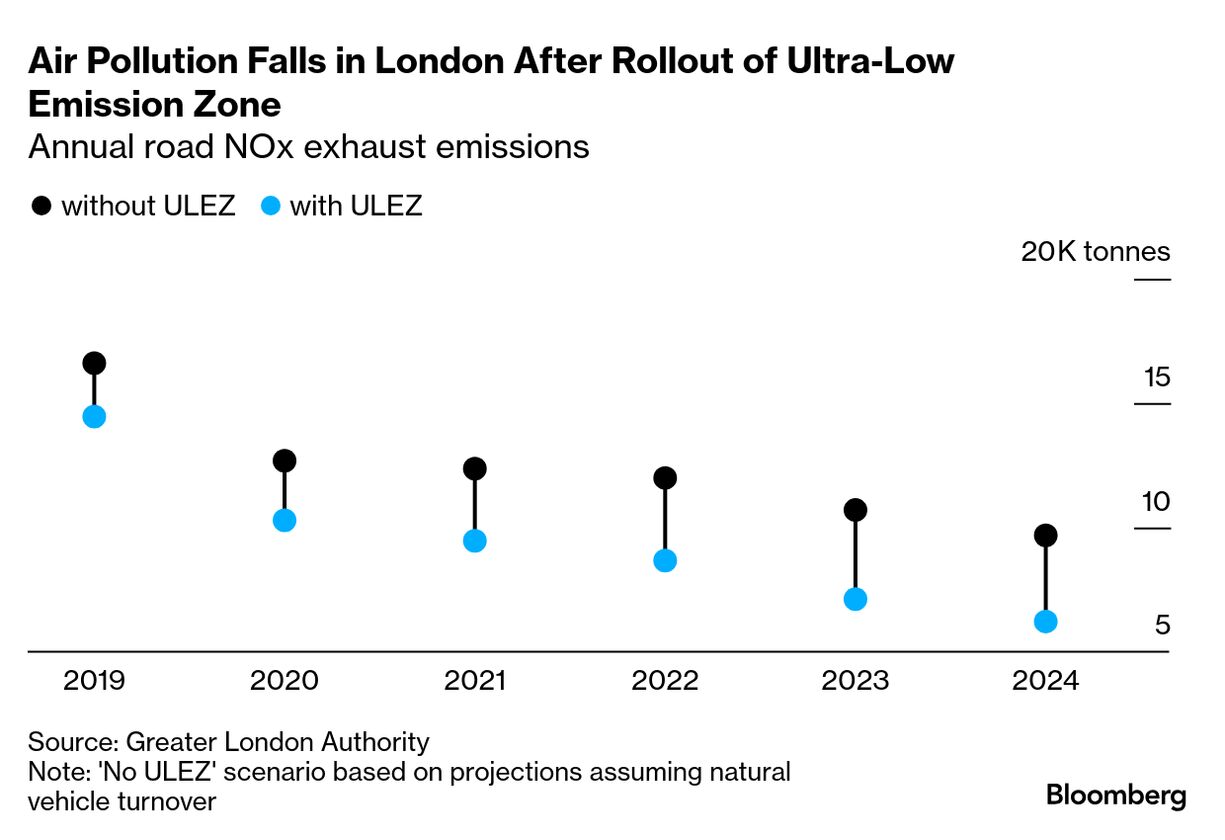

| Next week Bloomberg Green will look at how the climate tech industry is navigating US President Donald Trump’s tariffs and environmental policies. On Earth Day, Bloomberg's Akshat Rathi will speak with Michelle Ma, Jennifer Dlouhy and Alastair Marsh to discuss the latest and answer questions from Bloomberg digital subscribers and Terminal clients. Listen in to our Live Q&A on April 22 at 10:30am EDT here. The traffic report from London | By Olivia Rudgard As you load up your car and head off on your long weekend away, it might surprise you to learn that, for the last few years in London, one topic has dominated elections, campaign events, protests and politics. It’s not knife crime, house prices or the cost of living. No – it’s traffic, and most particularly, an ultra-low emission zone expanded by London mayor Sadiq Khan, from the center-left Labour Party. Cars – how and where we use them, and how much they cost to drive – make for powerful politics. And telling people that it’s going to be harder or more expensive for them to use their car has caused some serious controversy in the past few years, particularly in three global cities: New York, Paris and London. In the UK, the ultra-low emission zone, which charges drivers of older and more polluting vehicles a daily fee, was blamed for a surprise election victory in a local race close to London for the Conservative candidate, who had campaigned in opposition to the zone. That result, which came down to just 1.6% of the vote, prompted a radical policy rethink by then Prime Minister Rishi Sunak.  Vehicles travel along the A13 arterial road in London. Photographer: Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg The result changed the battle lines of British politics. Sunak pledged a crackdown on what he called “anti-car measures,” including limiting the ability of other cities to introduce policies restricting where vehicles could go. Sunak and his Conservative government campaigned hard on this u-turn, as well as a rollback of climate policy, in last year’s national election. (They lost.) New Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch has since pledged to scrap Britain's net zero by 2050 target altogether. Of course, ULEZ – and car restrictions more generally – aren’t the only policies prompting opposition from right-wing parties in some parts of the world. But they have become a flashpoint for politicians campaigning to block what they say is an unfair limitation. That’s how US President Donald Trump’s Republican Party has criticized New York City’s charging zone, and how opponents to Parisian Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s traffic-limiting measures have described her policies. So it’s instructive, then, to look at what these policies have actually achieved so far. There’s data from all three schemes suggesting that there are benefits to be found, in better air quality, quicker journeys and lower congestion. In London, data suggests that commerce within the zone’s limits haven’t suffered because of the car pollution controls – as some feared – and that over 90% of cars and vans are now compliant with the emissions rules. This suggests that drivers have taken advantage of grants offered by the mayor to replace a polluting vehicle with a cleaner one. Some of the biggest improvements in air quality were in the outer London boroughs that opposed the expansion.  There are still a lot of unknowns, of course, particularly on the long-term effects on air quality, fairness and businesses. And other cities that are much further down the path of reducing emissions from traffic have found that curbing tailpipe pollution only takes you so far. Other pollutants, like stoves and furnaces, industry and agriculture, also affect air quality, and electric cars, while zero emission from the exhaust, still contribute pollution from brake and tire wear. But London, as well as New York and Paris, as I write today, hold lessons for policymakers and their constituents on what could be in store if their cities also attempt to control traffic congestion. Developing countries require trillions of dollars a year to transition to clean energy and build climate-resilient infrastructure. So where will the money come from? Avinash Persaud, special adviser on climate risks to the president of the Inter-American Development Bank, joins Zero to make the case for giving more money to Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), which already funnel hundreds of billions of dollars a year to poorer countries around the globe, much of which goes to climate projects. His pitch is now harder than ever to make as the US slashes international climate finance and European countries reduce their overseas aid budgets to support defense spending. Listen to the full episode and learn more about Zero here. Subscribe on Apple or Spotify to stay on top of new episodes.  Avinash Persaud Photographer: Hollie Adams/Bloomberg |