|

|

Today, in Alexandria, Virginia, a senior federal judge from South Carolina, Cameron Currie, heard oral argument on consolidated motions filed by former FBI Director Jim Comey and New York Attorney General Letitia James in their separate criminal prosecutions. Both of them filed motions challenging the legitimacy of Trump’s insurance-lawyer-turned-U.S. Attorney Lindsey Halligan’s role in their prosecution. Here’s what you need to know ahead of what Judge Currie said would be a pre-Thanksgiving decision:

The motions are being heard by Judge Currie, who was appointed by the chief judge of the Fourth Circuit (where Virginia and South Carolina are both located), since it would be problematic to have a judge from the same district where a U.S. attorney has been putatively installed consider whether the appointment was proper.

It’s reassuring to know that some people still care about ethics and conflicts of interest.

Appearing for the Justice Department, attorney Henry Whitaker told the court that any questions about the appointment of Halligan involved, at worst, mere paperwork errors. Whitaker was the Florida Solicitor General until earlier this year. He clerked for Justice Clarence Thomas after law school and worked in the Office of Legal Counsel during the first Trump administration.

Perhaps anticipating problems with the validity of Halligan’s appointment, Attorney General Pam Bondi tried to back-bless the indictments, filing that she had reviewed the grand jury proceedings. But the Judge pointed out this morning that wasn’t possible because they hadn’t been fully transcribed. And, while every attorney general would likely have loved to possess a magic wand that would permit them to fix errors after the fact, that’s not how any of this works. Prosecutors must follow the rules, which are in place to ensure that defendants’ rights are protected and justice is done. Cases are dismissed when they make procedural errors, in part to protect them and in part to deter prosecutors from making future errors. If ever an attorney general needed that sort of a reminder from the courts, it’s this one.

Politico characterized the hearing this way: “A federal judge expressed deep skepticism Thursday about whether a federal prosecutor handpicked by President Donald Trump to bring criminal cases against his political rivals was legally appointed to the role.”

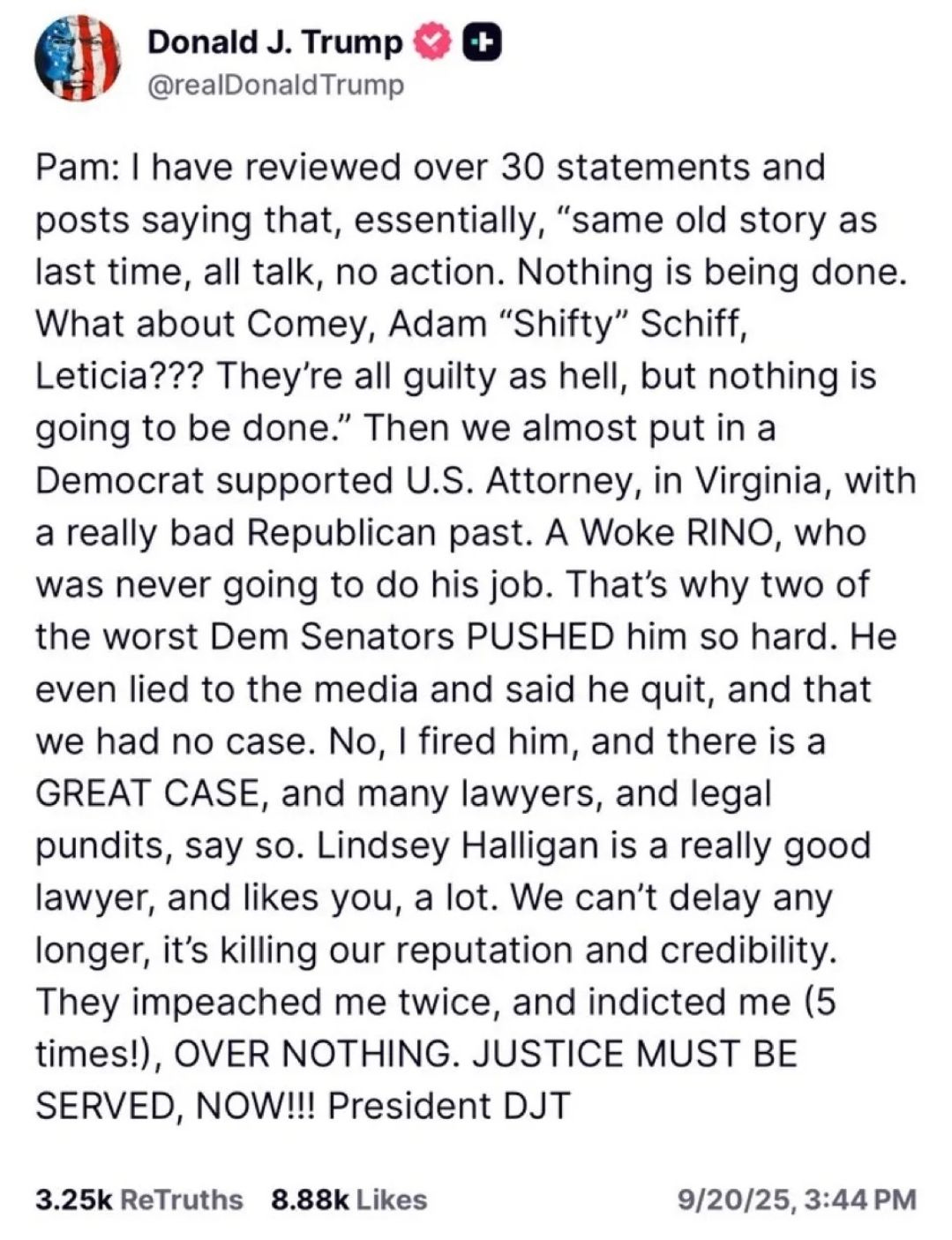

We all know the history by now. Trump’s handpicked appointee to be U.S. Attorney in the Eastern District of Virginia, longtime, highly regarded prosecutor Erik Siebert, concluded there was insufficient evidence to indict either Comey or James. His removal and replacement with Halligan followed. Along the way, Trump stumbled, publicly posting what looked like a text message meant for Attorney General Pam Bondi:

“JUSTICE MUST BE SERVED, NOW”

Bondi, apparently persuaded, put Halligan in place, and Halligan promptly indicted Comey, just barely ahead of the expiration of the statute of limitations, following up with the indictment of James.

The allegations that her appointment is improper have to do with the technicalities of the Vacancies Reform Act, which allows a president to replace a vacant U.S. attorney with an appointee for 120 days, after which the district court appoints an acting U.S. attorney until a presidentially appointed, Senate-confirmed nominee is put in place. Halligan’s predecessor had already been in place for 120 days when he was removed to make way for Halligan. But the government seems to be suggesting that it can swap out different people for sequential 120-day terms under the law. The defendants’ lawyers argued that if the government can continue making these interim appointments, it could perpetually avoid the constitutional requirement that the Senate confirm U.S. attorney nominees. That would give a president an open invitation to install unqualified loyalists instead of professional prosecutors for these important positions. Under the extreme facts of this case, the defendants have asked the Judge to dismiss the prosecutions with prejudice to deter future maneuvering like this.

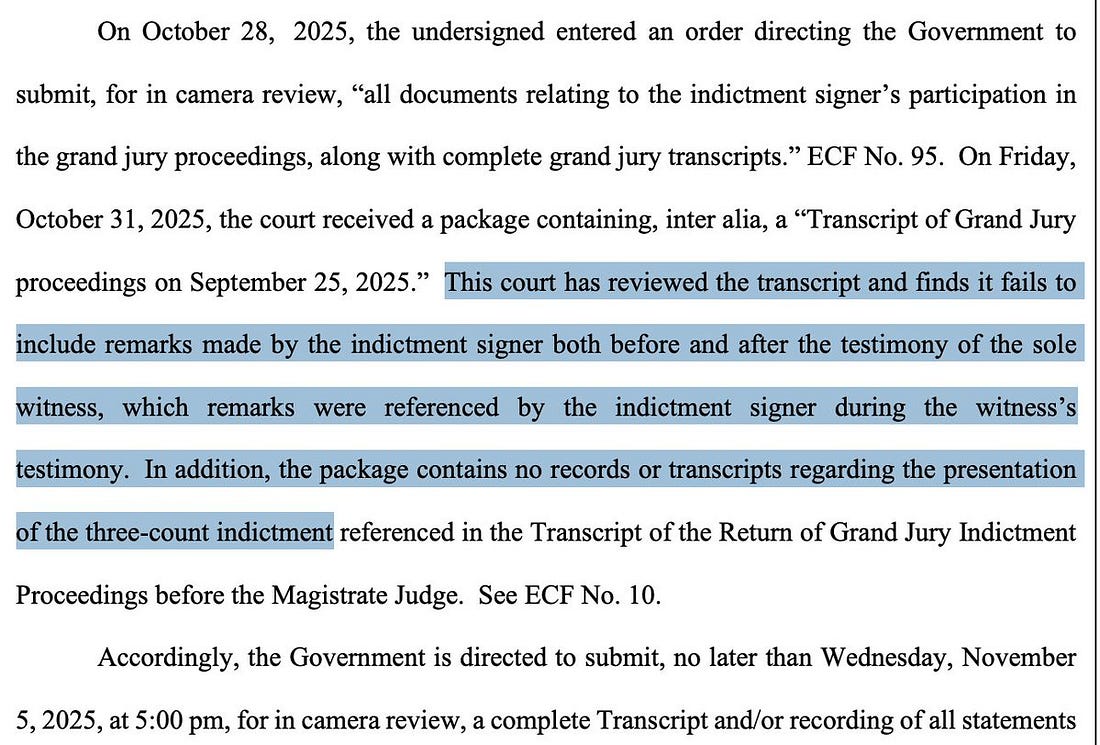

One particularly interesting exchange in court this morning occurred when Currie pointed out that the grand jury transcripts the government turned over to her in advance of the hearing for her review were missing parts of Halligan’s interactions with the grand jurors. Why excise those sensitive portions of the proceedings? We don’t know, so we’ll stick a pin in it for now. But there are strict rules governing prosecutors’ interactions with grand jurors and it’s not beyond the realm of possibility that someone with no prosecutorial experience could have transgressed them.

This hearing came on the heels of a hearing before the magistrate judge who is handling preliminary motions in the Comey case. The government has asked for a filter team to evaluate evidence obtained in an unrelated investigation, filtering out any material that may be subject to the attorney client privilege so prosecutors can use the rest of it. That hearing didn’t go well for the government, with the judge ordering grand jury “minutes,” a confidential transcript, turned over to the defense. He scolded the government attorneys for the rushed prosecution, characterizing the behavior as “indict first, investigate second.”

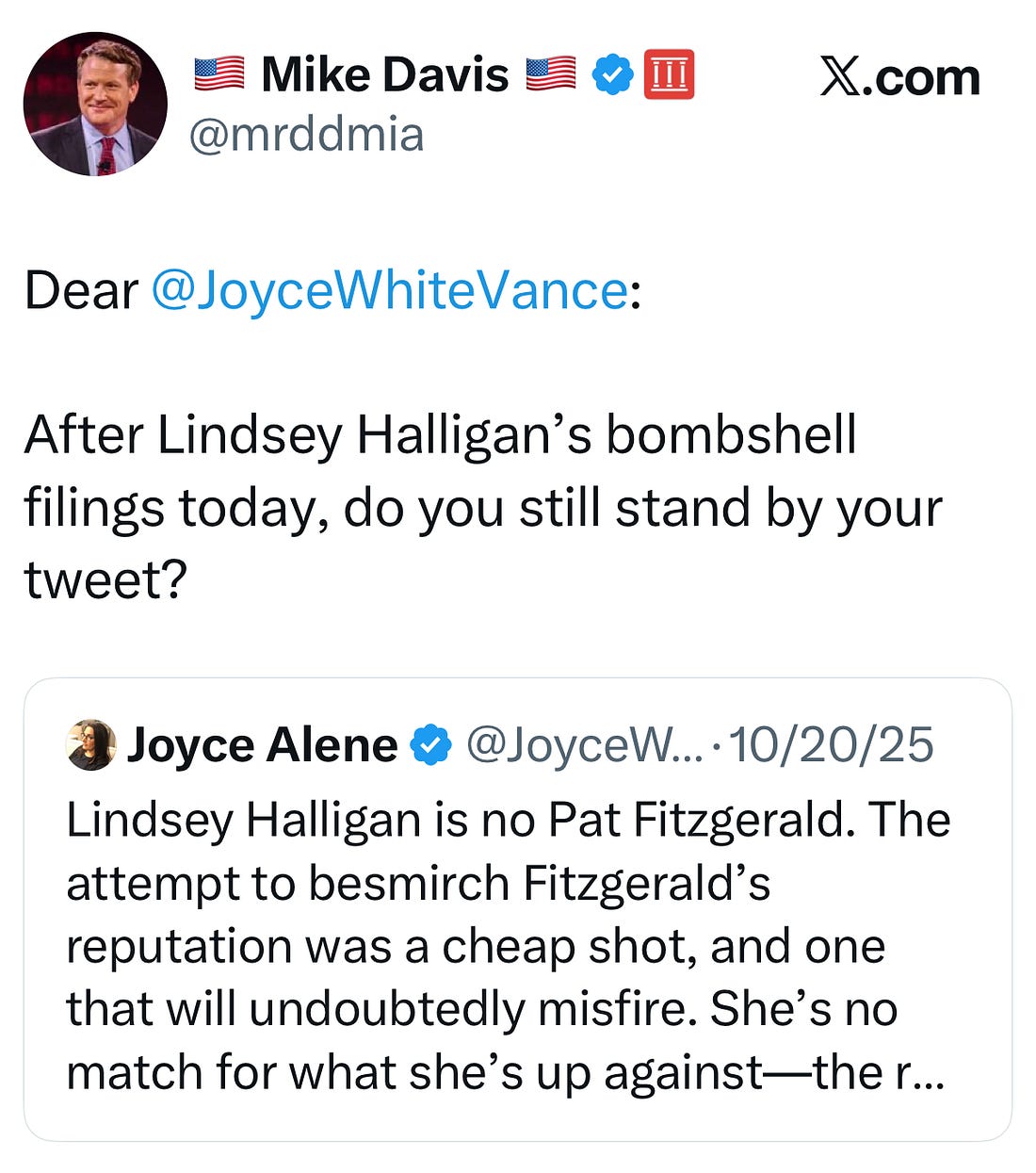

And a Trump-loyalist amen choir on Twitter has been trying to reinforce the case against allegations that it is a selective and vindictive prosecution brought against one of the key people Trump includes among his enemies. Like this tweet from MAGA operative, lawyer Mike Davis.

It’s a cheap effort to tarnish Comey in the public eye. The claim Davis is making, even if it were true, is not what Comey is charged with. But Davis seems to specialize in attempted intimidations.

For the record, I responded with one word, “yes.”

Back to the courts—they don’t seem to be on Halligan’s side, so far, in any of these proceedings. In my experience, it’s unusual for a court to authorize disclosure of a prosecutor’s comments in the grand jury. And never good news for the government. It’s also not good news for the government that they failed to provide it in the first place—the inference that could be drawn is they didn’t want the court to see it… for some reason.

But what the Comey case may come down to, when all of the motions practice is over, is the basic flaw in an indictment that was rushed by someone with no prior experience as a prosecutor. Comey has argued, among other points, that he can’t be prosecuted for a statement that, legally, can’t be false. He’s charged with saying he stood by his prior testimony. Even if the case goes to trial, there will be a motion to dismiss the case at the close of the government’s evidence on this basis. Based on what we currently know, it’s hard to see how the government could respond.