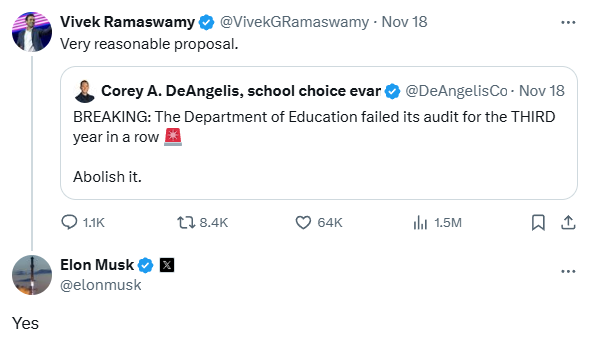

| During his campaign, President-elect Donald Trump repeatedly promised to eliminate the US Department of Education. Doing so, he said in a September 2023 video message, would get rid of “waste and corruption” and people “that in many cases hate our children,” and return “all education work and needs back to the states.” On X, Vivek Ramaswamy and Elon Musk, whom Trump has tasked with running the newly formed advisory committee, the Department of Government Efficiency, approved of this plan.  Trump took his first step toward making good on his campaign promise this week, selecting Linda McMahon, chairwoman of conservative thinktank the America First Policy Institute, to head the Department of Education. Beyond briefly serving on the Connecticut State Board of Education, McMahon has no formal teaching or education experience; she spent 29 years as the chief executive of World Wrestling Entertainment. McMahon’s been a major donor to Trump’s various Presidential campaigns; he named her head of the Small Business Administration during his first term. “We will send Education BACK TO THE STATES, and Linda will spearhead that effort,” Trump said in a statement, announcing her appointment. Of course, education curricula and school funding formulas are already decided at the state level — which is why states have wildly different educational approaches. California, for example, requires students to pass an ethnic studies class before they graduate high school while Oklahoma recently ordered 55,000 Bibles for its classrooms. If the education department were eliminated, those ethnic studies and Bible orders would remain in place. So what would change? As far as federal agencies go, the education department is tiny. It has fewer than 4,500 employees — the smallest staff of any cabinet-level agency — and this year is operating on a $90 billion budget, which sounds like a lot of money until you realize that it’s less than 11% of what the US spends on the military ($824 billion this year). Elon Musk is currently estimated to be worth about $300 billion — or more than three US Department of Education budgets. Despite its small stature, the DOE is charged with some pretty monumental tasks. It allocates Title I funding to low-income schools in an effort to reduce the inequality that results from the states’ reliance on local property taxes for the bulk of public school funding. (On the whole, about 13.6% of public school funding in the US comes from the federal government, but that figure is higher for schools in low-income areas.) It also funds programs for students with disabilities, overseas compliance of Title IX which bans sex-based discrimination in education, collects and standardizes student achievement data, oversees federal student loans, and more. In many situations, education experts say, there is no way to make states take over these tasks. “You’d still have a $1.7 trillion student loan program. By law, the federal government has an obligation to oversee civil rights in K-12 schools. You’d still have to do that,” says Jon Fansmith, senior vice president of government relations at the American Council on Education. What would actually happen, Fansmith says, is that the DOE’s most vital programs would be shifted to other departments. The Department of Justice might oversee Title IX and civil rights complaints; the US Treasury might take over student loans. But then, that isn’t really eliminating anything, it’s just shuffling things around in a giant federal government reorg that would decentralize education oversight and may worsen bureaucracy. “What’s being contemplated may be a great sound bite but it’s a terrible policy,” says Fansmith. But let’s say the DOE really is eliminated, and that the work it does disappears. This newsletter isn’t long enough to explore the myriad effects that would have on public education and the economy, so I’ll just focus on one thing: financial aid. Specifically, Pell Grants. The Pell Grant program is the largest federal grant program for higher education. Its mission is simple: to help children from poor families pay for college. Pell grants are provided to students on a sliding scale based on their family’s ability to pay college fees. As long as students meet basic criteria such as not dropping out of college, the money does not have to be repaid. Much like the K-12 school voucher programs that Republicans champion, the money isn’t tied to a specific institution; a student can use their Pell grant money at whatever school they decide to attend, be it their local community college or an Ivy League university. Now, the Pell Grant program isn’t perfect. When Pell Grants first started, they were enough to cover about 80% of the average tuition at a four-year college, but over the decades Congress has repeatedly failed to allocate enough money to allow the program to keep pace with inflation, much less skyrocketing college tuition prices. Today, a Pell grant maxes out at $7,395, or less than a third of the standard college tuition price. Still, the Pell Grant remains the most important federal program that helps children from poor families afford university. Since its creation in 1972, Pell Grants have helped more than 80 million Americans. Many Pell recipients are students of color and also the first member of their family to go to college. The program costs about $32 billion a year, or more than a third of the DOE’s budget. (Or one tenth of Elon Musk’s estimated wealth.) If the DOE were eliminated and Pell grants disappeared, college would become considerably more expensive for low-income students. “The easiest conclusion is that you’d have a lot fewer low-income students at colleges,” says Fansmith. This runs counter to the goal of many conservatives. Last year, when the US Supreme Court ruled that race can no longer be considered in college admissions, it suggested that socioeconomic diversity was laudable, and one best achieved without focusing on race. “If an applicant has less financial means,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his concurring opinion, “then surely a university may take that into account.” But a recent Harvard Crimson investigation found that 1 out of 11 Harvard undergraduates came from just 21 high schools — this in a country with more than 23,000 high schools. More than half of these 21 schools are elite private schools with tuition costing as much as $67,000 a year. The public schools on the list are either located in an affluent residential area, require students to test into a magnet-style program, or both. Currently, only 20% of Harvard undergraduates are Pell Grant recipients. If the DOE and therefore Pell grants were eliminated, that number would likely shrink. Elite schools like Harvard would skew even more affluent. But it’s not that children from poor families will be less likely to attend Harvard; they’ll be less likely to attend college at all. This has grave implications for their future earnings potential. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, people with only a high school diploma make 56% of what people with a bachelor’s degree do. Some of the most popular male-dominated jobs that don’t require a college degree, such as truck driving and manufacturing, have seen their real wages decline in recent decades, meaning they actually pay less than they used to. If kids from poor families can’t afford to go to college, they’re more likely to be locked into these low-paying jobs, which means their children will also grow up poor. Black, Latino, and Native American families have higher rates of poverty than White families in the US, but you don’t have to stratify poverty by race to understand why it harms children and families — which is why, for 50 years, the DOE has been offering Pell Grants. Trump has only railed against the DOE in general; he has not targeted Pell Grants, so maybe they’d continue in some form. “There has been some conversation about block grants, and allowing states to decide how to distribute funds,” says Wil Del Pilar, senior vice president at the education research group Education Trust. But Del Pilar says that may not be such a great idea, either. To explain why, he points to historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), which tend to admit twice as many Pell-eligible students as non-HBCU institutions, and yet are chronically underfunded at the state level, especially in the South. In fact, a 2021 report by the Tennessee Office of Legislative Budget Analysis found that between 1957 and 2007, the state had shortchanged Tennessee State University, an HBCU, by as much as $544 million. “Absent federal guardrails, we’d be going back to a system we’ve already tried,” says Del Pilar. “And we know how that works out.” |