- Long-term investors need to check their assumptions.

- Hopes for private equity look worryingly optimistic.

- Japan is getting ready for higher rates as it keeps moving in the opposite direction from everyone else.

- AND: Oscar Wilde was right that it’s important to be earnest.

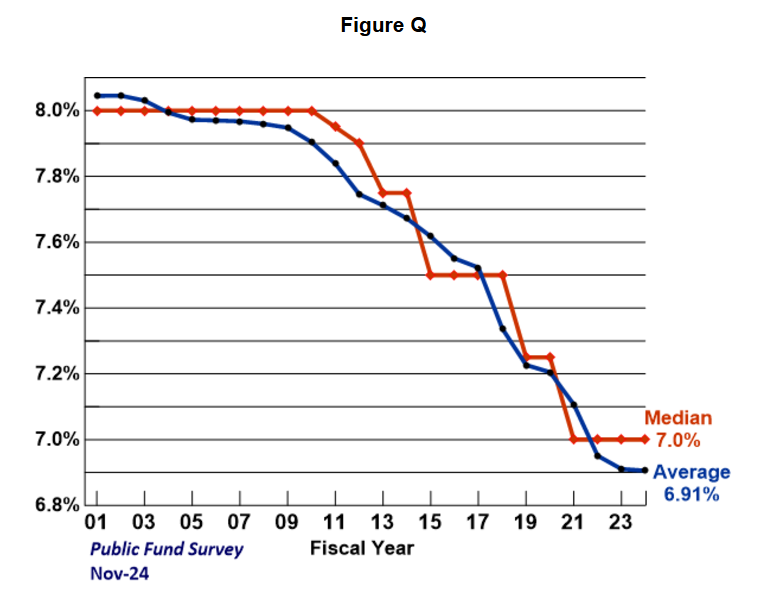

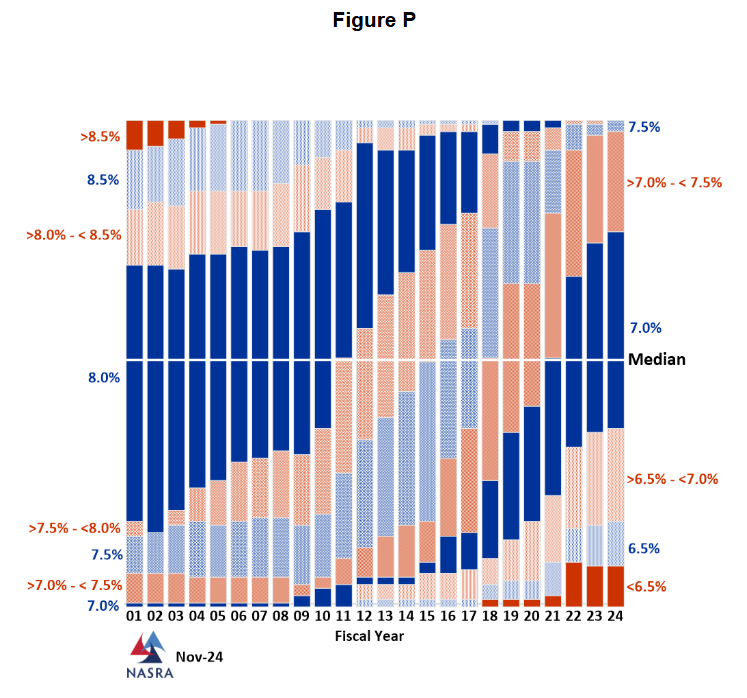

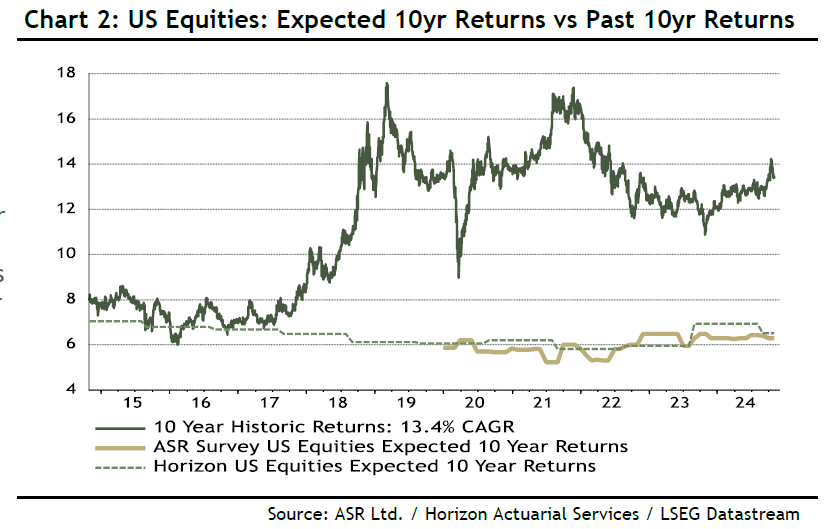

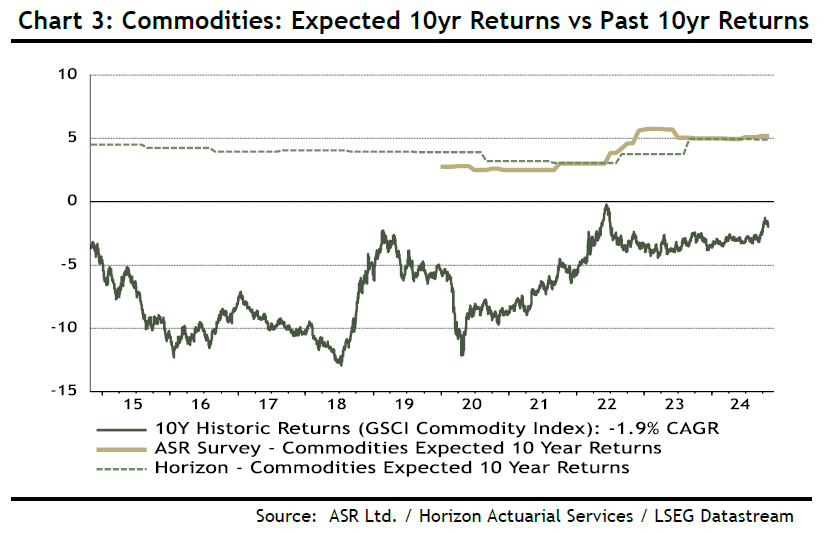

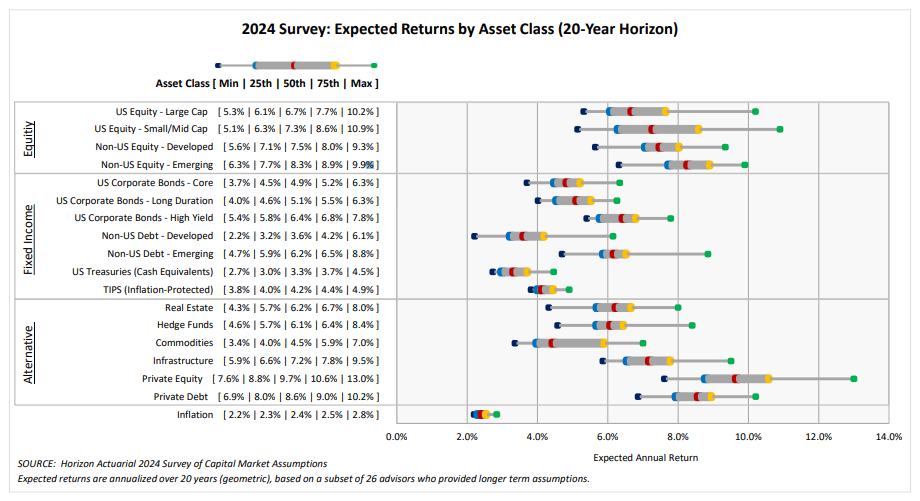

This is the the season when investment houses publish their forecasts for the coming year, and I excoriate them as a waste of time. Not only is it silly to spend time looking at arbitary short time periods, but for most institutions, it’s the very long term that really matters. So as we get ready for the download of 2025 projections that will probably have to be revised half a dozen times before the year is over, it’s worth looking at the rather different cottage industry that produces long-term capital assumptions. The depressing takeaway is that this seems also to be a waste of time, with the projections so perfunctory that you wonder whether they were taking Keynes’ dictum about the long run too much to heart. They shouldn’t, as many institutions should be planning over horizons far beyond a human lifespan. In theory, very long-term projections should be driven more than anything else by the starting point. When stocks look historically expensive, expect the subsequent decade to be worse than the average, and vice versa. There are also sharply different ways to approach asset allocation, so you would expect a variation in approach. Instead, what emerges is: 1) remarkable stability in projections over time; 2) a tendency to herd around a few round numbers, and 3) an odd belief that some asset classes can do well regardless of circumstances — particularly private equity. My friends at Absolute Strategy Research have pulled together capital market assumptions from a number of sources, and in the process dug up a couple of other regular attempts to gauge long-term forecasts: a survey published by Horizon Actuarial, and one conducted by Nasdaq eVestment. Calling the returns for asset classes over the next decade isn’t quite as popular as predicting where the S&P 500 will be on Dec. 31 next year, but it’s close. These assumptions are most important in the world of US public pensions, where you can make a big deficit go away by assuming higher returns. (There’s more to pension accounting than that, but that’s a fair summary.) NASRA (the National Association of State Retirement Administrators) publishes a survey here. The mean and median predictions for equity returns have come down in this century, but very steadily, and not by that much. The axes on this chart of projected 10-year annualized equity returns go from 8.0% to 6.8%:  Source: NASRA Public Fund Survey NASRA also has this chart of how the total range of assumptions has moved over time. It has never been more than 1.5 percentage points, and the direction of travel has been the same:  Source: NASRA Public Fund Survey This might seem like an appropriately steady and conservative view of the equity market, but remember that the biggest determinant of your return is the starting point. Return expectations were highest right at the beginning of 2000, when stocks were absurdly over-expensive and obviously destined for a bad few years. Expectations had declined a bit 10 years later, when stocks were cheap. This doesn’t reflect prudence and conservatism as much as a dogged refusal to take any notice of changing circumstances. This is how 10-year total returns from the S&P have moved since 1980. The shape is completely different from the pension funds’ projections, and it’s odd that there was little attempt to gauge the potential for very big swings in returns. It’s unreasonable to expect pension trustees to time the market, but assumptions that grew more bearish and then bullish according to the starting point would have made sense, and helped them catch contrarian opportunities: To show how little use these unbending assumptions are in practice, David Bowers and Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research compiled the following chart comparing the average 10-year projected return for US equities according to their own survey and to Horizon’s, with the outturn. Huge variations in returns have been greeted with no alteration in assumptions for the future:  Source: Absolute Strategy Research For commodities, it’s the other way around. The last decade has been really bad for for investing in them, but nothing can shift the assumption that they will make 4% or 5%:  Source: Absolute Strategy Research Another troublesome finding is what looks like a naive confidence that private equity will keep producing returns that aren’t available for anyone else. This chart, from Horizon’s survey, shows 20-year projections for a range of asset classes. Private equity sticks out like a sore thumb as, in a somewhat different way, does the universal assumption that inflation will average between 2% and 3% for the next two decades:  Source: Horizon Actuarial All the surveys find a virtually universal belief that private equity and credit will continue to outperform well into the future. Why exactly would we expect that? Leverage is unlikely to be as cheap as it was for most of the post-crisis decade, taking away a critical basis for the sector’s outperformance. And there is far more money in private equity now. That means more competition to do deals, which will ultimately be on better terms for sellers and worse terms for investors. Assuming private equity can keep outperforming for another 20 years is questionable. And if so many institutions really are embedding the assumption that PE can do just that in perpetuity, that will mean more money sloshing into the sector, making it that much harder to achieve those returns. Politicians and everyone else ceaselessly praise the merits of long-termism, but somehow in practice it’s always the immediate and short-term that is given priority. That’s a natural human failing, which is close to inevitable. But it’s disconcerting to see that even the institutions that really must plan a long way into the future are still so perfunctory in their long-term thinking. Ordinarily, a central bank governor stressing data dependency ahead of a monetary policy meeting is a non-story. However, the market’s reaction can sometimes tell a lot about the perceived direction of rates. Bank of Japan Governor Kazuo Ueda’s comments on Thursday offer a perfect example. He said it was “impossible to predict the outcome of the meeting at this point,” which seems anodyne but left his options wide open. The yen’s subsequent appreciation, however, showed that many in the market think the data might well justify a hike. The currency’s lackluster performance saw it recently top 156 per dollar, the weakest since August. That weighs on import costs and inflation, so a hike isn’t hard to justify. Ueda seemed to endorse this approach by emphasizing the importance the BOJ places on the exchange rate. Unsurprisingly, the yen responded favorably, climbing almost 1% at one point:  The 10-year Japanese Government Bond yield also got a boost. Yields rose to the highest since July and are close to breaking to a level not seen in decades: For investors, the rising JGB yields suggest that they can begin to narrow their differential with US equivalents. BCA Research’s Dhaval Joshi describes this gap as reaching an “unsustainable extreme” in plunging to negative 3% earlier in 2024, after oscillating between -1% and +1% for most of this century. This BCA chart highlights differentials at unprecedented levels in the past two years: This gap can be traced to the divergence in interest rate policies between the two countries. Japan persisted with its zero interest rate policy until March, while inflation had forced the US to exit its pandemic-induced, rock-bottom rates far earlier. This continues to keep financial conditions easier for everyone, as Japan becomes a ready source of cheap funding. Can this split at least be brought back to more normal levels? Possibly. Joshi argues that inflation expectations would first have to come together: If Japanese and US inflation expectations are converging, then the nominal interest rate differential cannot remain so diverged. And if the nominal interest rate differential can remain so divergent, it means that inflation expectations will have to un-converge. Either way, the deeply negative Japan-US real yield differential is anomalous and unsustainable.

Inflation meanwhile came in above the central bank’s target, though price gains moderated a bit. Consumer prices excluding fresh food rose 2.3% in October from a year earlier, down from 2.4% in September, government data showed Friday. That was above the consensus estimate of 2.2%. This inflation is greater than many Japanese have known in their lifetimes.

While a weak yen and moderate price increases make a case for a December hike, there’s a chance the central bank may skip if its hawkish words buy more time. Tough-talking to quell speculators was deployed earlier this year before the Ministry of Finance made a $63 billion intervention to prop up the currency. Another reason for a skip, Bloomberg Economics’ Taro Kimura argues, is that BOJ policymakers likely want to avoid making waves amid political uncertainty following the ruling coalition’s loss in general elections last month. They will also need time to gain more insight into the US economy’s trajectory after Trump’s win and assess how the Federal Reserve may respond: Our view is that the BOJ will make its next rate hike at its January meeting when it will release its next quarterly report on growth and inflation. This will give it an opportunity to build its case for withdrawing stimulus further with an in-depth analysis of the US economy and domestic inflation momentum.

The BOJ’s march to a 1% policy rate is still on. Whatever happens at next month’s meeting, Ueda’s data dependency approach lets investors in on the central bank’s thought process. In conditions that many investors have never experienced before, that’s no bad thing. —Richard Abbey It’s important to be earnest. I’ve just been lucky enough to see a preview of the National Theatre’s new production of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest in London, and it’s brilliant. Hugely camped up with a multiracial cast (Lady Bracknell is now a particularly imposing Jamaican lady, and she’s terrifying), the characters can be heard singing tunes from One Direction and Miley Cyrus. Sometimes things like this are crass. In this case, it was hard to escape the feeling that this is just the treatment Wilde would have loved to give it, if only he’d been allowed to in Victorian England. Points of Return will now take a week off while I get some vacation in England and Richard sees his family in Ghana. Enjoy the week and if you’re in the States or celebrating elsewhere, have a great Thanksgiving.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |