| Central banks’ climbdown from the post-pandemic inflation peaks commenced amid both optimism and trepidation. As 2024 draws to a close, reality has set in, trepidation is triumphing, and rates have been recalibrated accordingly. This was true even before the Federal Reserve’s strongly hawkish meeting this week. It’s become customary to compare rate campaigns with scaling mountains. A year ago, the hope was that rates would make a Matterhorn peak (diagonally up and then straight back down again), rather than a Table Mountain with a long plateau. Now, central banks seem to be navigating a mesa with high interest rates and occasional plateaus punctuated by cliffs. It is still premature, alas, to declare victory over inflation. And coordination among central banks — vital for safety, just as it is for mountaineers on a descent — has proved hard to achieve. At this point, policymakers have a fair idea of the nature of the monster that is post-pandemic inflation, and why it’s been difficult to slay. The following chart was produced using the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function, which derives implicit policy rate probabilities from futures and swaps prices, and shows the expected course of rates against what transpired. In brief, the growing economic strength of the US compared to everyone else steadily drove central banks into different courses. The dollar’s onslaught explains much of the problem. In this latest installment of our series tracking the central banks' response to inflation, we continue assessing their coordination with the help of colleagues Richard Abbey, Carolyn Silverman and Elaine He. Read our maiden edition here, and subsequent editions here, here, here, here, and here. Now, with the task still incomplete, central banks — roped together for safety — must decide how to approach a Donald Trump presidency committed to an economic agenda that seems more likely to raise inflation than reduce it. That is causing big fissures. Canada and Switzerland have cut by more than had been expected this year, while the Bank of Japan — facing very different conditions — has raised rates somewhat more than predicted. The Federal Reserve, Bank of England and the European Central Bank have made far less progress than hoped. In the US, a strong consumer and resilient labor market kept the Fed from cutting until September. Bond yields stayed high, ensuring the strength of the world’s reserve currency. That helped the US press down on inflation, but had the opposite effect on everyone else: Central bankers outside the US complain about the strong dollar, a problem intensified by the Fed’s hawkish December meeting. Nikko Asset Management's Naomi Fink notes as long as risk appetite persists, the dollar will draw support from wide yield differentials compared to other countries. But nervousness about the US and its fiscal position has prompted a search for other havens, notably gold. The latest budget brinkmanship in Congress can only exacerbate this. Fink said: The rally in gold prices thus far has been less about risk aversion and more about the frantic search among global investors for an alternative to US Treasuries, particularly one that can be held as foreign reserves and serve as a hedge to risk portfolios. The inversion of the US yield curve made dollar cash alternatives attractive, given that even short-term paper offers a healthy premium over many other developed and even some developing market currencies.

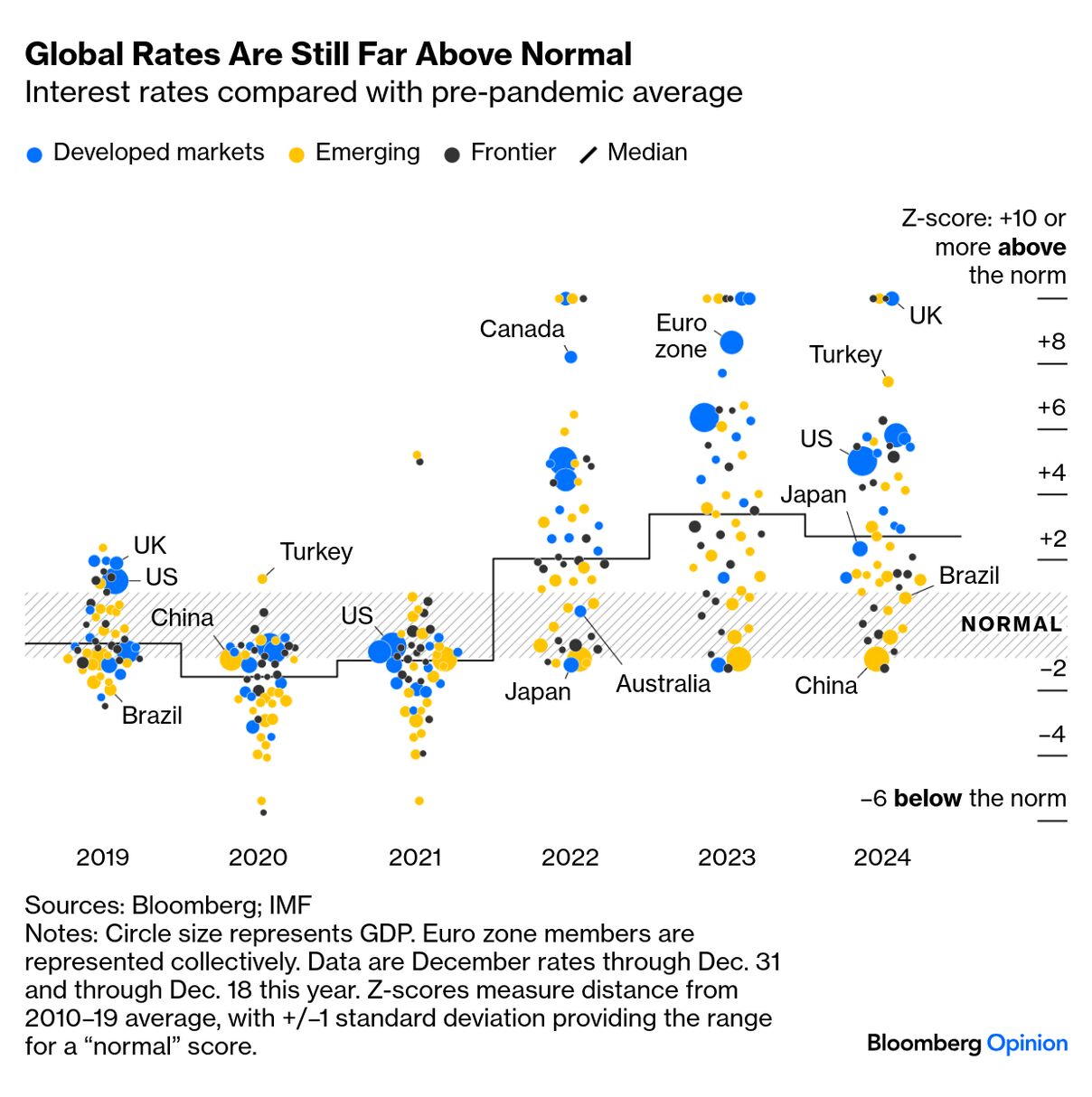

Across the border, Mexico’s central bank has since March eased rates by a full percentage point, the same amount as the Fed. While Banxico’s easing cycle is supported by inflation decelerating in line with the central bank’s target, Trump’s proposed 25% tariffs on Mexican imports could complicate things. The peso has already dropped 16.5% against the dollar this year and additional levies would deepen its woes. The problems created by the strong dollar — which is ending the year at a high — help explain one of our clearest conclusions, which is that rates remain a long way above pre-pandemic levels, despite substantial reductions in inflation. Rates are lower but the descent has been painfully slow. Particularly by the standards of the pre-pandemic decade, they remain very, very high in the developed world. The huge global exception is China, where rates have stayed well below the norm throughout:  This project uses a Z-score approach. Countries’ rates are measured by how far they differ, using standard deviations, from their own norm in the decade from 2010 to 2019. A figure two standard deviations above the mean will happen only 2.5% of the time. Higher numbers indicate ever lower probabilities. The idea is to capture the intensity of the shock for the developed economies when rates rose after a decade of being held very low. As the cluster of large blue bubbles in the chart demonstrates, the developed world still has rates way above that norm. A country like Brazil, which this month hiked by a full percentage point as inflation ticked higher, has a long history of high inflation and interest rates and could swallow this much more easily than the US or the euro zone might have done. As its currency is now in virtual freefall against the dollar, that implies that more rate hikes could come quickly. Talk about hiking again is painfully disappointing after hopes for a rapid descent. There was an understanding that rates would stay there as long as necessary, combined with a hope that the pressure could be removed quickly once it was safe to do so. Where does this leave mountaineering? The Bank of England’s chief economist Huw Pill suggested last year that rates might move like Table Mountain, with a long plateau before the climbdown starts. Switzerland, ironically, is the country whose rates trajectory most resembles its iconic Matterhorn. And in most countries, what has resulted is more of a mesa with a flat peak, diagonal edges, and several plateaux on the way down: Nevertheless, monetary policy easing has been the norm this year. The number of central banks that cut rates has exceeded those hiking every month in 2024: The Fed arrived late but in style with September’s jumbo cut, but now faces the prospect of staying at a new plateau for a while. This is a repeating pattern. Central banks in developed markets were noticeably slower in their response to the inflation surge. As a result, the rates when they came inflicted much pain, and they had to wait before starting to cut. This year, nearly 80% of developed world central banks eased policy with the most notable exceptions being Japan — which exited the negative interest rates policy (NIRP) it had had in place since 2016 — and Norway and Australia, which held steady throughout the year. Meanwhile, emerging central banks’ response has grown more difficult. It’s not only Brazil that has had to start hiking again. The benefit they bought themselves by taking early action on price rises hasn’t lasted long:

All of this has come despite global progress on inflation. China is grappling with a slowdown and this perversely helps central bankers in the rest of the world by effectively exporting deflation. The US is the problem. The latest US CPI print shows disinflation stalling, even if great progress has been made from 2022’s peak of 9.1%: With inflation close to pre-pandemic levels, why are rates still so high? Populations the world over are furious about the explosion of price rises after the pandemic, obliging officials to err on the side of anti-inflationary caution. Consumer forecasts of price rises have fallen somewhat, but suggest that inflationary psychology hasn’t been snuffed out. Thus, central bankers can’t pat themselves on the back yet, even though inflation in most of the world is back at levels that can be considered normal: The other problem confronting central banks is politics. Anger over inflation has led to the fall of a range of incumbent governments during the year, while for 2025 Trump’s potential tariffs and their ramifications for import prices are a real concern. Fitch projects that tariff hikes will negatively impact the US as well as Canada, China, Mexico, Korea and Germany, with the global impact likely to be felt more fully in 2026. Fitch said: Tariffs will boost US inflation, which is still proving sticky. A crackdown on immigration could add to inflation by reducing labor supply growth, and we have raised our US inflation forecasts. Nevertheless, we still expect the Federal Reserve to bring rates down slowly towards neutral next year and expect 125 basis points of cuts by the end of 2025. But we no longer expect any further Fed rate cuts in 2026.

With politics unstable in a number of countries, anxiety over whether officials can get fiscal deficits under control is rising, while tariff uncertainty is compounded by robust US growth. As Katharine Neiss of PGIM Fixed Income notes, “If we continue to see this sort of US exceptionalism with the economy, then that would translate other things equal into a Fed that is higher for longer.” That would mean tighter global financial conditions to which other central banks would have to adapt. The selloff that followed this week’s "hawkish cut” by the Fed revealed the extent of the anxiety. Fed Chair Jerome Powell still forecasts two cuts next year, but the market is thrown by his admission that some FOMC members are already attempting to incorporate the impact of Trump 2.0 tariffs. Such an approach is prudent, but amps up uncertainty. Are tariff concerns overblown? The Trump 1.0 tariffs in 2018 had a muted inflationary impact, but price expectations were well anchored at the time. This chart suggested by research from Oxford Economics suggests that we should be careful with that analogy. Products hit by those tariffs did indeed see markedly higher inflation:  Despite all the tariff anxiety, DWS Group’s George Catrambone believes the impact on inflation will likely be minimal. He argues that the recent inflation spike has been supply-driven. Resolving supply chain troubles and maintaining a healthy labor supply have benefited price growth. That said, Catrambone says uncertainty surrounding the impending tariffs makes it hard to predict its impact: We don't know what policy will go through, and to have a hard time fundamentally with an electorate that overwhelmingly voiced the economy and inflation as their number-one concern, Trump running on being the champion against inflation and suddenly bringing inflationary policies back into the electorate, I think that's a challenge. I would take a much more cautious approach, trying to short Treasuries in advance of what tariffs Trump might actually put on.

There are other pockets of concern, notably the fiscal issues facing Germany and France, both of which have recently seen their governments fall. The International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook sees near-term global growth as stable with the balance of risks tilted to the downside. For all the excitement about the US and the hopes that artificial intelligence can spark a new rise in productivity, the descent has been disappointing and continues to be dangerous. But critically, the central bankers did get through the year without a major accident, and tamed inflation somewhat while they did it. Methodology [1]

Survival Tips

I've had requests for a Christmas playlist. Trying to keep to things that are a little off the beaten track, my favorite off-the-wall Christmas novelty records are Wombling Merry Christmas by the Wombles, and Nellie the Elephant by the Toy Dolls. For some Christmas carols that are actually worth listening to, to my taste, try Adam Lay Ybounden and the Coventry Carol, and for classical takes try Berlioz' L'Enfance du Christ, Ariel Ramierez's Navidad Nuestra, or Bach's Christmas Oratorio. (OK that one's not far off the beaten path). Or Blue Xmas by Miles Davis. That concludes Points of Return for this year. We'll be back in your inbox with the trades that Hindsight Capital LLC made this year over the holiday season, and back in the first week of January. Thanks to all who subscribe, and we'll do our best to be worth reading again in 2025. Have a happy holiday season everyone. |