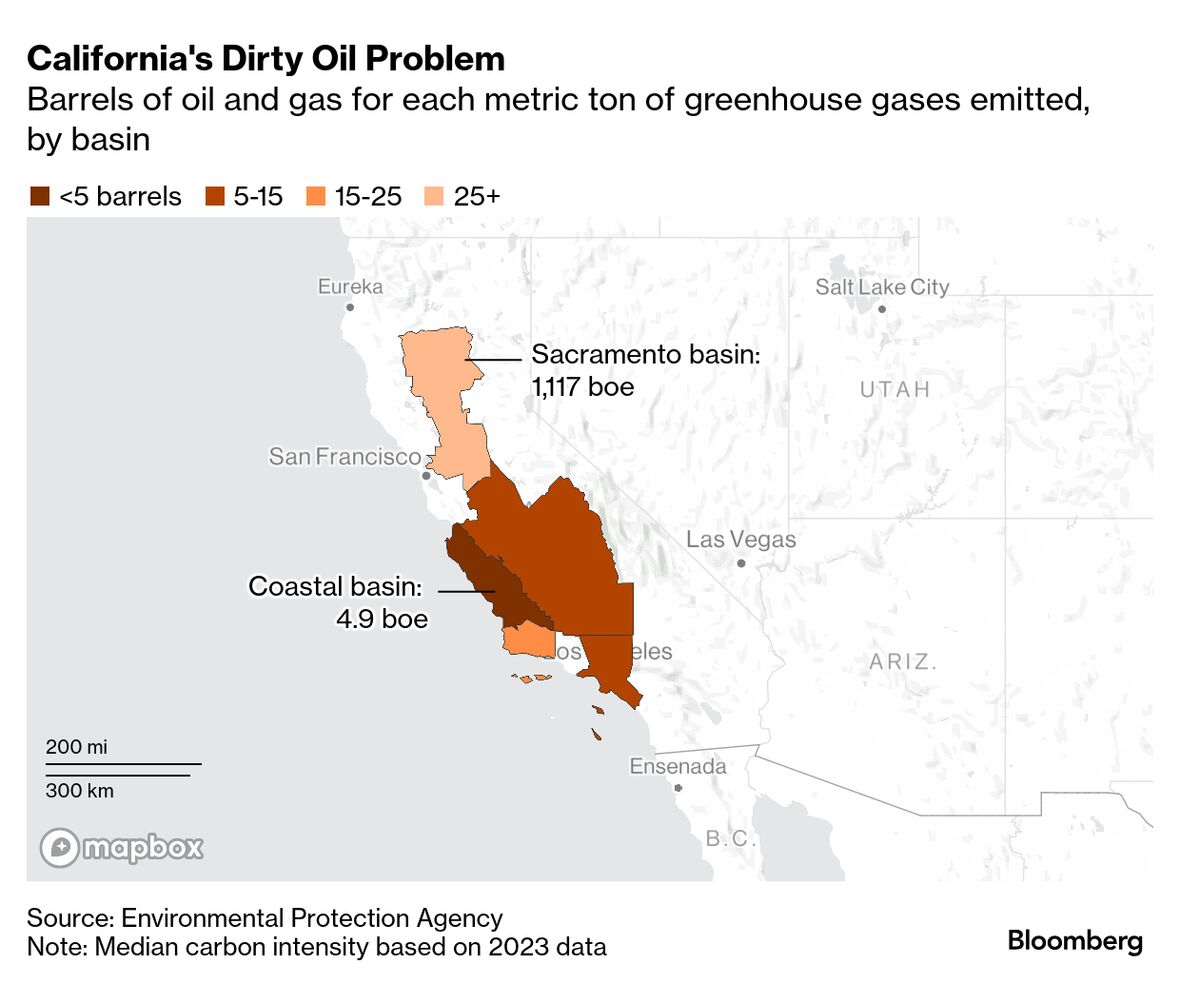

| By Robert Tuttle In California’s San Joaquin Valley, old-fashioned pump jacks eke out a trickle of crude that’s among the dirtiest in America. Powering the oil field equipment are solar panels that generate state carbon credits potentially worth nearly $2 million. E&B Natural Resources Management Corp., the local oil producer that built the solar plant, is among a handful of little-known companies that produce the most emissions-intensive crude in the US, according to an analysis by Bloomberg News. Yet the solar array offers an incentive to keep pumping at a time when California is aggressively trying to phase out fossil-fuel use. The situation exposes a paradox in the state’s carbon-trading system: By offering oil producers credits for their renewable energy use, California effectively is subsidizing drillers who produce as few as five barrels of oil and gas for every metric ton of greenhouse gases they emit, according to Bloomberg’s analysis. That compares to a US average of about 165 barrels of oil per metric ton.  It’s an irony with implications beyond the Golden State. California, with its ambitious climate goals, has long been a model for slashing emissions. But it’s also a state disconnected from the main oil-refining and -producing regions of the US, largely reliant on imports by tankers and local production to keep gas tanks running. That’s given drillers a foothold in a state that is, at times, openly hostile to the oil industry. And it underscores a challenge the rest of the US is facing: How to combat global warming when rising oil demand continues to keep even the dirtiest crude flowing from the ground. An analysis of data from the Environmental Protection Agency and California Air Resources Board show not only that California is home to some of the most polluting oil, but that drillers behind solar projects that receive credits under the state's carbon-trading system, called the Low Carbon Fuel Standard, or LCFS, are operating some of the most carbon-intensive oil and gas facilities in the US. (Read the methodology used to estimate the value of carbon credits and companies’ emissions intensity online.) Closely held Sentinel Resources Inc., E&B Natural Resources Management Corp. and Grade 6 Oil LLC manage assets that were among six of the 10 most carbon-intensive oil and gas operations in the country. Sentinel and E&B Natural Resources built solar plants, making them eligible to participate in the carbon trading system. The California Independent Petroleum Association, which represents E&B and other state producers, disputed the EPA’s published emissions data. “EPA data is unaudited, unverified, and largely based on estimates, default values, or, in many cases, entirely unreported,” said Rock Zierman, chief operating officer of the association. “Relying on such flawed data to draw conclusions is misleading and inaccurate.” An EPA spokesperson, in response, said that emissions reporting is mandatory and subject to a multi-step data verification process. The LCFS, created 15 years ago to cut emissions, requires oil refiners to buy credits generated by lower-carbon fuel producers, mostly ethanol and biodiesel companies. It includes a carve-out for local drillers, giving them credits for using “innovative crude oil production methods” that cut emissions at the well site. Since 2016, oil drillers have submitted 18 solar projects and 15 have been approved, according to state data. California’s Air Resources Board defends the LCFS program as an “effective piece of California’s transition from petroleum to increasingly clean fuels” by reducing emissions associated with steam injection, which increases carbon intensity, Lys Mendez, a spokesperson for the agency, said by email. “To be clear, this is not a state subsidy.” While LCFS credits earned by oil companies amount to less than a fraction of 1% of the total credits generated under the program, the nearly 27,000 generated last year would have earned more than $2 million at the average credit price, according to state data. “This is a very ironic situation,” said Paasha Mahdavi, associate professor of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. "This entire standard was designed to reduce emissions in the state.” Instead, it’s “creating the unintended consequence of prolonging oil production.” Read the full story with estimates for how much solar projects can offset emissions from oil drilling in California on Bloomberg.com. |