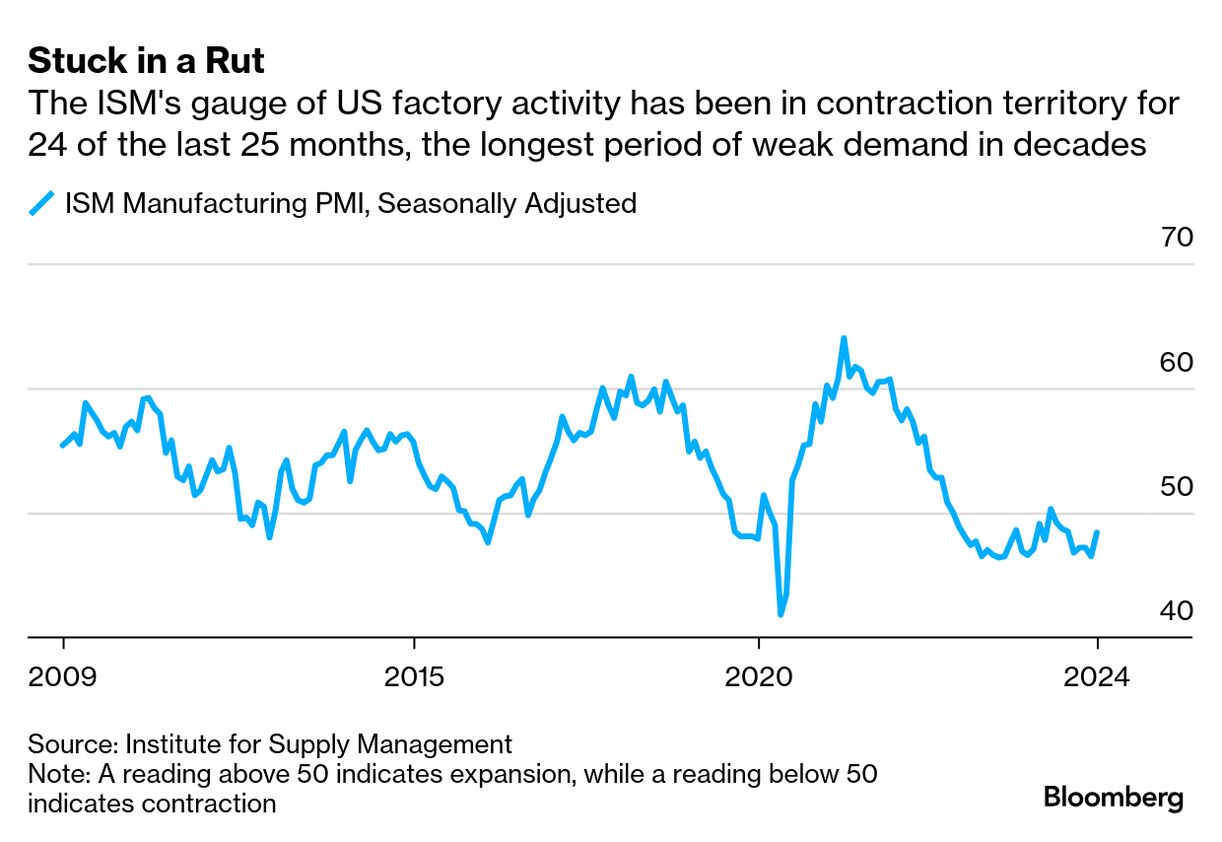

| Have thoughts or feedback? Anything I missed this week? Email me at bsutherland7@bloomberg.net. Also, a programming note: This is the last Industrial Strength for the year. Look for the next one on Jan. 10. Thank you for reading and happy holidays! To get Industrial Strength delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here. It’s the time of year for making predictions, but that’s especially hard to do right now for a manufacturing industry squeezed between the promise of a recovery and the threat of tariffs. US manufacturing activity has been in a contraction for the better part of two years, according to the Institute for Supply Management’s benchmark measure. A persistent hangover from inventory stockpiling during the pandemic supply-chain crunch collided with higher interest rates and inflated prices to dampen demand for new equipment. It’s the longest period of weak demand since at least the early 2000s when the dot-com bubble burst. The Federal Reserve’s measure of US industrial production has declined in 14 out of the last 18 months on a year-over-year basis.  Eventually industrial demand should start to perk up, and that recovery is expected to take hold in 2025. But even before accounting for tariffs or other disruptions, the improvements are expected to be gradual: sharp rebounds follow sharp downturns, and that’s not what happened here, outside of a few select markets such as European air conditioners and warehouse automation, says Barclays Plc analyst Julian Mitchell. He expects sales on average to rise 4% next year for multi-industrial companies, compared to 2% growth this year. Read more: Rolling Factory Funk Tees Up Earnings Gloom It’s not exactly the dawn of a manufacturing super-cycle but the Industrial Select Sector SPDR Fund hit a record in late November on optimism that lower interest rates and rollbacks of taxes and regulations under President-elect Donald Trump would accelerate the recovery. That benchmark has since cratered 8% so far in December, perhaps on the realization that expectations about the direction of interest rates had gotten too rosy, says Wolfe Research analyst Nigel Coe. Federal Reserve officials this week lowered the benchmark interest rate for a third consecutive time but trimmed their expectations for further reductions next year, signaling concerns over the path of inflation. Some policymakers have begun to incorporate the potential impact of Trump’s proposed tariffs into their economic assessments, even as the ultimate policy remains something of a question mark, Chair Jerome Powell said in a press conference. “It’s kind of common sense thinking that when the path is uncertain, you go a little bit slower,” Powell said. “It’s not unlike driving on a foggy night or walking into a dark room of furniture. You just slow down.” Those are apt metaphors for the future facing industrial companies as well. It’s safe to say that there will be new tariffs of some kind on goods shipped from top US trade partners upon Trump’s return to the White House, but no one really knows how extensive or damaging they might actually be. The president has latitude to carve out exceptions by product code that could more narrowly tailor tariffs to areas of strategic concern, such as Chinese companies using Mexico as a sort of backdoor into the US. But he also has latitude to take a broad brush and wreak havoc on US supply chains, and so far at least, he seems bent on the latter approach. Read more: ‘Nobody Knows What’s Going to Happen’: CEOs Brace for More Trump

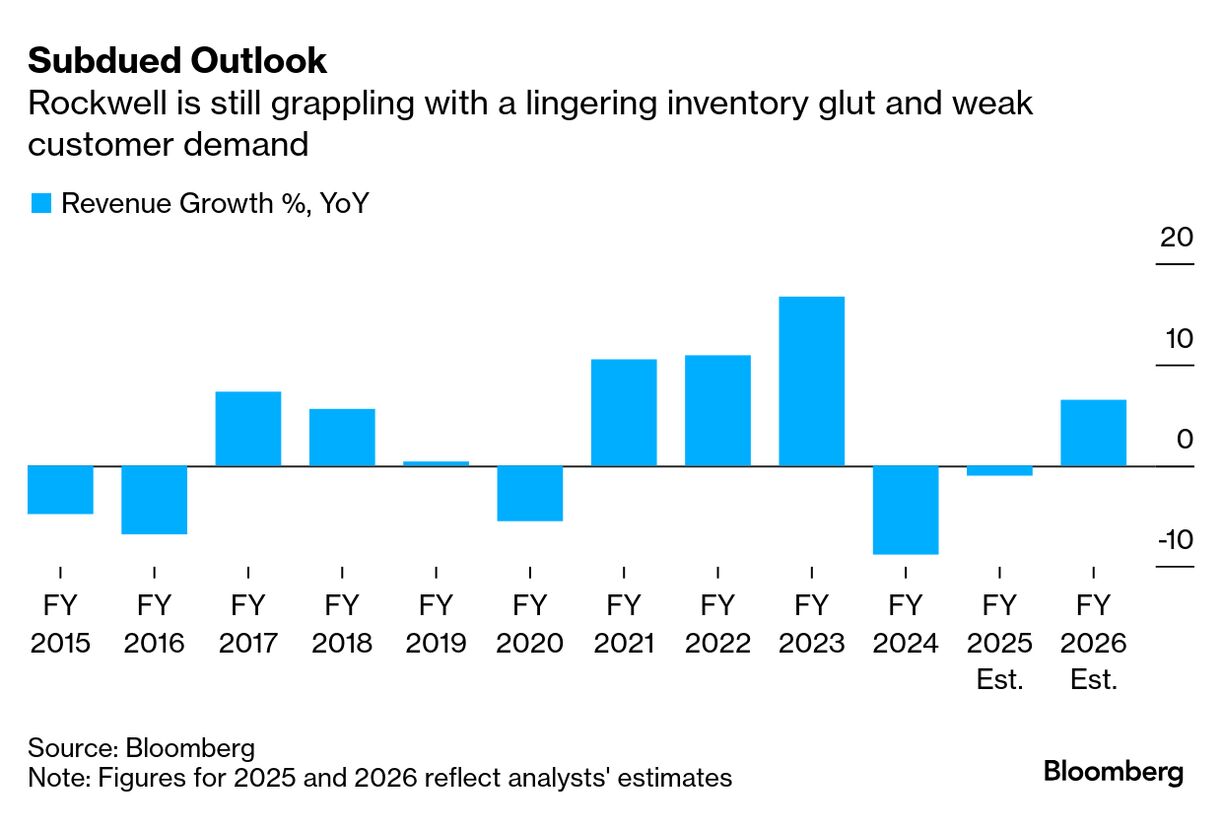

Trump, whose inauguration is scheduled for Jan. 20, has pledged to put 25% tariffs on all goods coming from Mexico and Canada on his first day in office unless the countries do more to stop the flow of migrants and the opioid fentanyl into the US. He’s also threatened as much as a 60% tax on Chinese imports (plus a 10% top off over concerns about illegal drugs) and a 10%-to-20% levy on trade with everyone else. “We know who's going to be in the White House next year, but what happens on January 20th, and in the couple days after that, matters,” Rockwell Automation Inc. Chief Executive Officer Blake Moret said in an interview. “There's a range of possibilities, and I think taking those comments literally is an important scenario that manufacturers should be prepared for.” Manufacturers often rely on automation equipment — such as that which Rockwell sells — to make bringing factory work back to the US economically palatable. While Rockwell benefited from a surge of US factory spending coming out of the pandemic, sales fell about 9% last year as the company worked through an inventory glut and customers delayed projects amid uncertainty over the Biden administration’s signature stimulus deals in clean energy and semiconductor manufacturing. That “muted environment” is set to linger into 2025, Moret said. Rockwell’s guidance calls for anywhere between a 4% decline in sales next year to a 2% recovery.  It’s unlikely that tariffs will immediately unlock a wave of fresh US manufacturing investments that would cause a spike in demand for industrial products, Moret said. Rewiring supply chains takes time; many companies are just now opening factories that were meant to reduce their reliance on China after the last trade war. Unfortunately for them, most of those sites are in Mexico, where labor was cheaper and plentiful and the trade relationship with the US was (up until recently) more of a sure thing. Rockwell itself has long had manufacturing operations in Mexico that are responsible for making configured-to-order systems that are sold both locally in Latin America and shipped to Europe, Asia and the US. When the company struggled to churn out enough automation equipment to meet demand coming out of the pandemic, it made capital investments in the US that Rockwell could lean on to add more capacity locally in the event of tariffs on Mexican imports, Moret said. “It’s not going to put everything overnight in the US, but it is a help as we look at having maximum flexibility in that manufacturing footprint,” he said. Should Trump actually proceed with the levies he has promised on trade with Mexico and Canada, most US manufacturers will be affected because supply chains in the three countries are so heavily integrated and interconnected, said John Lee, CEO of MKS Instruments Inc., an Andover, Massachusetts-based company that makes equipment used in the production of semiconductors and associated advanced electronics packaging. Tariffs are a tax paid by US importers and would drive up their costs. Read more: Tariff Bluster and Reality Jolt Factories “You never know with this president. It sounds like rhetoric, but then he actually does things with it,” Lee said. “If tariffs were on everybody, we're all going to have a lot of inflation. The whole world will live poorly. So I think there will be motivation to not have that happen. I don't think any president wants to have 15% inflation even for a short period of time.” MKS, which has a market value of about $7 billion, operates two manufacturing sites in California and five in Massachusetts, among others in the US. Despite the high cost of living in these states, it’s worthwhile to keep the intellectual property involved in certain production processes within arms reach, Lee said. But MKS also has a large facility in Mexico that was established in the early 2000s because the company was worried about finding enough skilled labor here at home. MKS imports components to the Mexico site for final assembly and then exports them back to the US, with products crossing the border “a few times,” he said. The Mexico factory makes products used in semiconductor manufacturing, such as pressure measurement tools, gas analyzers and isolation valves — similar to what MKS produces at some of its Massachusetts sites. “But the reality is we need both of those locations. It's not one or the other,” said Dave Henry, the company’s executive vice president of operations and corporate marketing. In October, MKS broke ground on a new factory in Malaysia to support future demand growth for semiconductor equipment used in wafer fabrication and help curb its dependence on China. President Joe Biden enacted sweeping US export control restrictions on products sold for advanced semiconductor applications starting in 2022, which shaved as much as $250 million off MKS’s revenue. “We'll sell what we can until we can't,” Lee said. “If people need a certain amount of chips, they’ve got to get made somewhere.” The company is also building a new chemical plant in Thailand to support its advanced electronics packaging business after many of its customers shifted their own production to Southeast Asia. “For the last 25 years, every factory that was built, was built in China — from every multinational as well as local Chinese companies,” Lee said. “For the last five years — and for the next 10 or five, who knows — every factory that would've been built in China, will not be built in China.” Honeywell International Inc., one of the last industrial conglomerates, is mulling a breakup that could result in the separation of its aerospace business. Activist investor Elliott Investment Management called on Honeywell to consider such a move last month as it announced a more than $5 billion stake in the company. Honeywell said the potential aerospace carve-out is under consideration as part of a strategic review that began earlier this year and has already resulted in a planned spinoff of its advanced materials arm and the sale of its face-mask unit. It plans to update investors again when it announces fourth-quarter earnings, which typically occurs in late January or early February. Read more: Honeywell Breakup Would Tee Up Megadeals The drumbeat of simplification has gotten increasingly louder for Honeywell after rivals including the former United Technologies Corp., General Electric Co. and Emerson Electric Co. orchestrated their own major breakups. There are no obvious duds among Honeywell's collection of businesses, and the company has a track record of steadily cranking up profit margins. But its sales growth has been lackluster relative to peers in recent years, weighed down by one business or another. It has often seemed like the company is trying to tell too many stories at once across its sprawling empire of aerospace, automation and energy assets. Should Honeywell proceed with a separation of its aerospace business, what will be left over is still a fairly jumbled mix of things like pressure gauges, building management systems, warehouse robots, fuel processing technologies and bar code scanners. That raises the question of whether a potential aerospace spinoff ultimately marks just the halfway point of Honeywell’s strategic review and if there could be yet more untangling left to come for this conglomerate. Read more: One Breakup Isn't Enough for Conglomerates Deals, Activists and Corporate Governance | Textron Inc. plans to pause production of snowmobiles and recreational off-road vehicles while it considers strategic options for the business. Sales in Textron’s specialized vehicle division — which includes the Arctic Cat power-sports equipment as well as golf carts and turf maintenance vehicles — have slid by about 14% through the first nine months of this year, compared with the same period in 2023. Consumer demand for power-sports equipment remains soft, Textron said. The company plans to take a pre-tax restructuring charge of as much as $35 million in the fourth quarter in connection with the production pause and will also write down as much as $40 million in inventory. The specialized vehicle business as a whole accounts for a relatively small overall share of revenue at Textron, which primarily makes private jets and helicopters.

GFL Environmental Inc., an $18 billion waste-hauling company, is in talks to sell its environmental services business to private equity firm Apollo Global Management Inc. for C$8 billion ($5.5 billion), the Globe and Mail reported, citing people familiar with the matter. Bloomberg News has previously reported that Apollo, EQT AB and Stonepeak were among the suitors for the GFL business. Activist investor ADW Capital Management earlier this year had called for GFL to sell the environmental services business and focus on solid-waste collection.

Forgital Group, an Italian manufacturer of forged components mainly for the aerospace sector, is swapping private equity owners. Stonepeak this week agreed to buy the business from Carlyle Group Inc. The business attracted several private equity suitors and was expected to be valued at more than €1.5 billion ($1.6 billion), Bloomberg News had previously reported. Terms of Stonepeak’s takeover weren’t disclosed. Carlyle acquired the business for €1 billion in 2019. Private equity firms have flocked to the aerospace manufacturing sector as stubborn supply chain challenges delay aircraft deliveries, forcing airlines to fly planes longer and pay up for spare parts. Private equity firms have announced at least $5.3 billion of deals in the sector this year, the highest since 2021, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. |