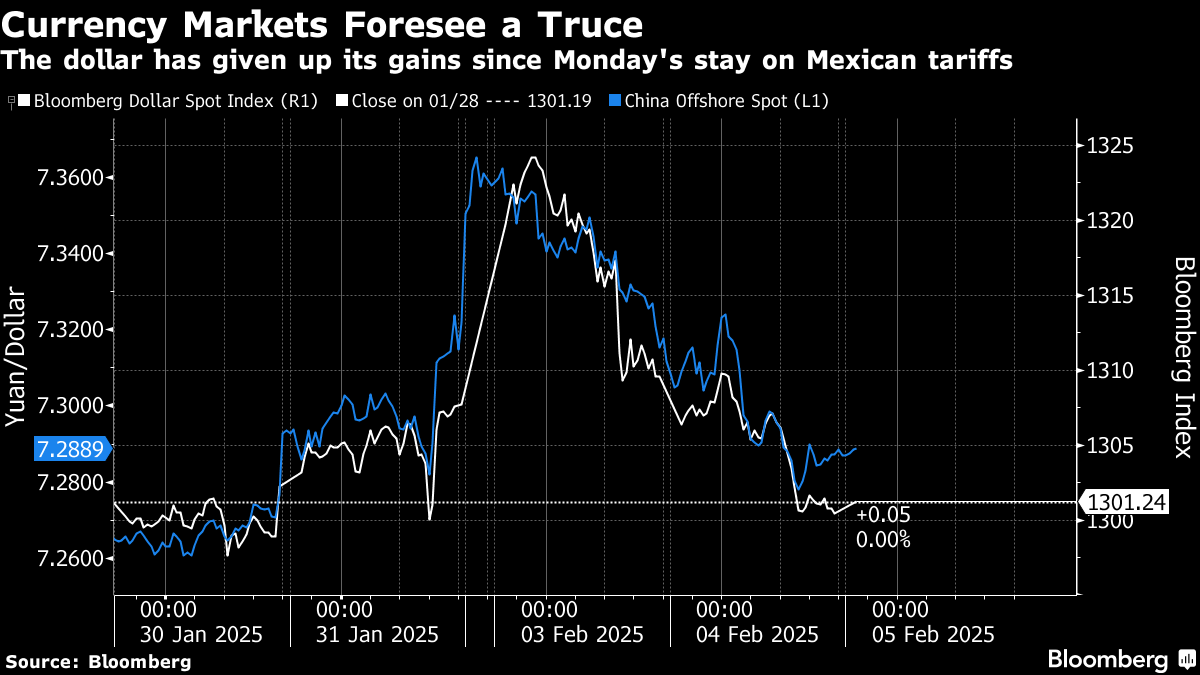

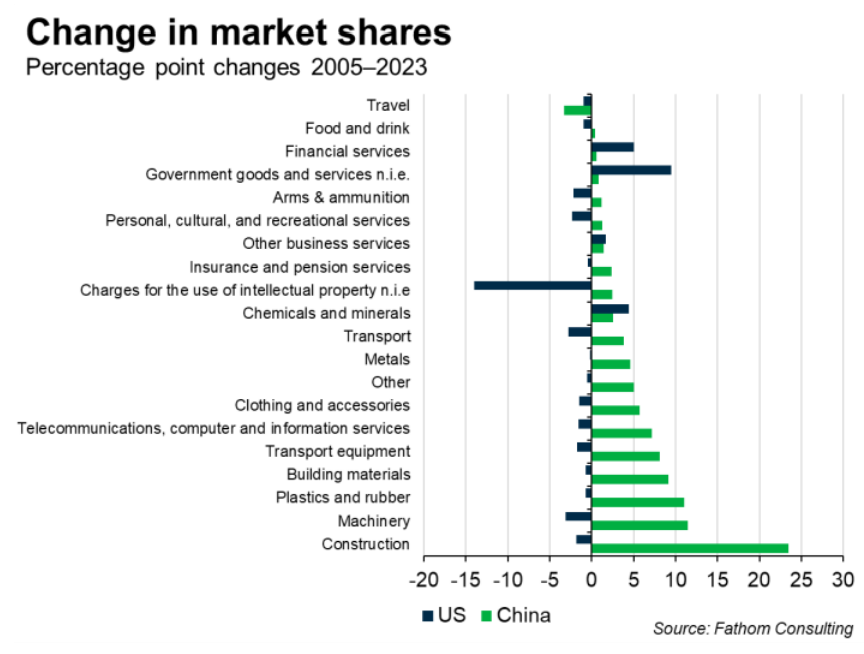

| Donald Trump and Xi Jinping are up to something, and Sun Tzu might be able to explain it. The ancient Chinese general, strategist and philosopher of war taught that “to subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.” That’s what both are trying to do. The intense question is whether they possibly can. Trump’s initial 10% tariff on all goods from Beijing — as opposed to the much more aggressive 60% he proposed during his presidential campaign — and China’s subsequent countermeasures show much less than the usual “animosity” between these two superpowers. The retaliatory tariffs, which target roughly 80 US products valued at $14 billion, don’t take effect until Feb. 10, while China added non-tariff measures including an antitrust investigation into Google, tightened export controls on critical minerals, and the addition of two US companies to its blacklist of unreliable entities. That’s not a robust response. Add in Trump’s brinkmanship with Mexico and Canada, which ended with no tariffs in return for largely symbolic concessions, and this leads to growing market confidence that this confrontation will soon go away. Trading in both the offshore Chinese yuan and the broader dollar suggest that Trump’s bluff is being called, with the spike after tariffs were announced last Friday now fully reversed:  The president, we know, is transactional. Beijing’s half-hearted retaliation suggests that Xi is merely sparring, not resorting to combat that could wreak lasting damage. Tuesday’s cancellation of a scheduled call between them seemed to muddy the waters. As Capital Economics’ Julian Evans-Pritchard points out, the underlying economic and political grievances with China run deeper than those between the US and its neighbors. De-escalating this confrontation will be harder. But Signum Global’s Andrew Bishop believes a deal is imminent. Beijing doesn’t want a trade war, he argues, given the prevailing weakness in its economy. He says that the onus for a deal is on Trump. First, the US needs to see how much China is prepared to “catch up” with the so-called Phase One trade deal signed under Trump in 2020. Further, the US wants to test Xi’s appetite for a “grand bargain” of the kind both he and his Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent have expressed an appetite for. Sun Tzu would probably approve.  Sun Tzu continues to influence Asian and Western cultures and politics. Source: Pictures from History/Universal Images Group/Getty Given China’s dependency on manufacturing exports while dealing with the overhang of debt in the property sector, a full-blown trade dispute is not in Xi’s interest. The timing works well for Trump. However, China’s manufacturing sector has made remarkable progress since the Trump 1.0 trade conflict and has reduced exposure to the US. Fathom’s Andrew Harris points out that between 2005 and 2023, China increased its global export market share in 19 of the 20 high-level goods and service sectors, while the US lost ground in 16 of them:  Source: Fathom Consulting This progress is not shocking. China’s entry to the World Trade Organization reduced export barriers. Still, Harris argues that the pattern is remarkable. Ordinarily, as a country becomes more integrated in the global economy, it would increasingly specialize in the sectors in which it is comparatively more efficient and rely on imports for others: China’s broad-based export expansion suggests that it does not adhere to this pattern, but instead is attempting to dominate export markets in all sectors simultaneously. This is particularly evident when you look at the pattern of Sino-US trade — while China has a large surplus in the sectors in which it is more specialized than the US (typically goods), it only runs small deficits in those in which the US is more specialized (typically service sectors).

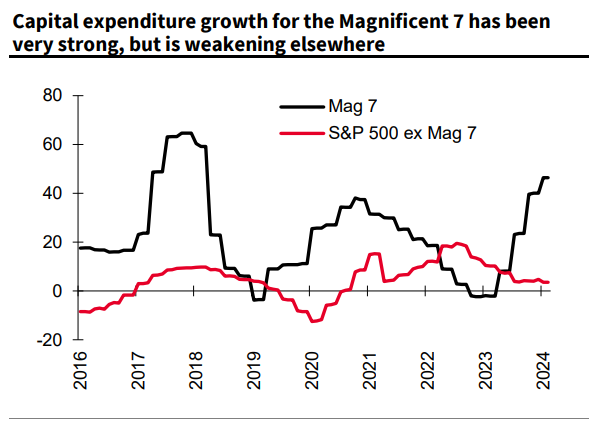

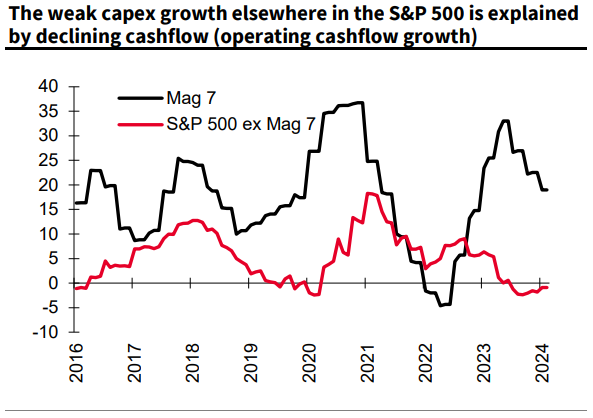

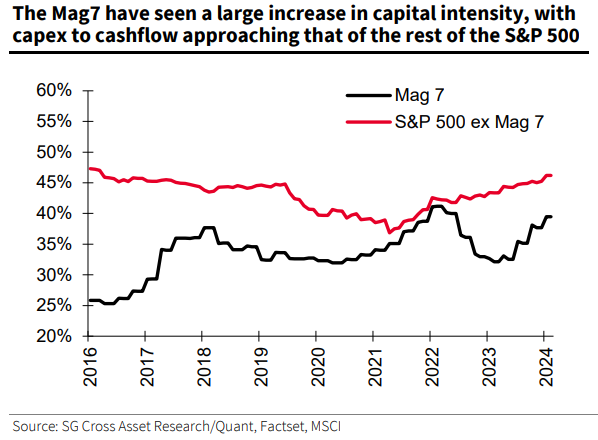

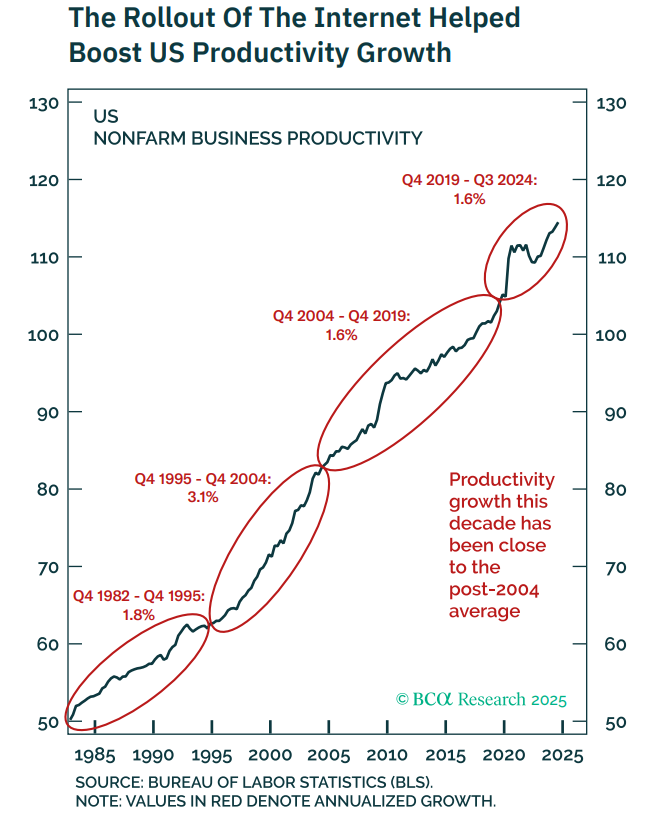

Further, Deutsche Bank AG’s Jim Reid points out that the US, despite accounting for 29% of global consumption, produces only 15% of the world's goods. China accounts for 32% of global manufacturing and just 12% of consumption: Both countries would like to change this. Perhaps China’s manufacturing economy wouldn’t be so much of a bother if the country had stuck to secondary or rudimentary products. But its relentless march toward the higher end causes consternation, while access to cheaper goods is no longer regarded as a “good trade” for the US. With the US unable to stop consuming far more than it makes, China may now find that it’s passed Sun Tzu’s point where conflict can be avoided — even if a short-term peace deal is on the horizon. — Richard Abbey The Ripples From DeepSeek | The ripples continue to spread from the DeepSeek splash. The arrival of a cheap and competitive Chinese artificial intelligence model shook assumptions. In particular, the belief that the dominance of the Magnificent Seven tech platforms could readily be transferred into similar dominance of AI is now in question. DeepSeek also shook confidence that their spectacular expenditures on building AI will ultimately prove justified. After the bell, Alphabet Inc., the holding company of Google, felt those ripples when traders greeted its fourth-quarter earnings with a sharp selloff. Revenues came in a tad below expectations and so its stock fell (as did Amazon.com Inc., the next Magnificent to report, and also heavily exposed to cloud computing): As the miss on revenues wasn’t that bad, the selloff showed that Big Tech is held to higher standards post-DeepSeek: Further, traders hated the news that this year’s capital expenditure could come in at an astronomical $75 billion. The prior estimate had been $57.9 billion. The growth in Alphabet’s capex since ChatGPT launched the AI arms race was already mind-blowing. Are these costs really justified? This matters. Andrew Lapthorne of Societe Generale SA shows that capex was already pretty much the only game in town, rising fast in the last two years, while expenditures by the other 493 non-Magnificents in the S&P 500 have dwindled:  Source: Societe Generale SA Lapthorne says that the Magnificent Seven have been raising capex “with the US dollar amount doubling over the last four years and running at 40% growth last year. However, the rest of the S&P 500 grew capex by just 3.5% last year.” The reason is that the other 493 aren’t pulling in much cash:  Source: Societe Generale SA However, Alphabet’s announcement suggests that their capital intensity will increase. More and more of the lovely cash they get from monopoly rents will go towards the AI arms race — and won’t therefore be available to distribute to shareholders:  Source: Societe Generale SA The capex boom unleashed by ChatGPT is hugely important then, but the vital question post-DeepSeek is whether it can really be justified. The Magnificents are largely spending on each other, which is fine as long as they can keep generating profits. But that leads to a deeper question about their business models. The parallels with the early years of the internet are instructive. It’s easy to forget now, but for the first decade after the arrival of the World Wide Web catapulted the internet into the public consciousness, the rap against it was that nobody could figure out how to make money out of it. The effect on productivity was dramatic, but companies didn’t start delivering profits in earnest until the burst of productivity growth was over. This chart is from Peter Berezin of BCA Research:  Source: BCA Research When the companies now known as the Magnificent Seven began to work out how to monetize the internet, Berezin says, “they did so by harnessing two economic forces that allowed them to create natural monopolies for their businesses: 1) network effects; and 2) economies of scale.” The network effects for social media or the Apple or Android ecosystems are obvious; you want to use them precisely because everyone else is. Similarly, software and web services enjoy a massive scale effect, as it costs a lot to write and then almost nothing to replicate. The problem for large language models, Berezin says, is that they enjoy neither. “If I use ChatGPT, it does not really matter to me if others use it too,” he says, disposing of network effects. The assumption pre-DeepSeek was that they had economies of scale, but “as it turns out, creating large language models may not be that expensive (especially if they are based on open source technologies). In contrast, using them on an ongoing basis is expensive, not just because of the pricey chips required for inference, but also because of the energy costs needed to run all those data centers where those chips are housed.” That leads to this devastating assessment: Large language models are a lot like airlines. Airlines are indispensable for global commerce but never seem to make much money because of their high operating costs and the fact that they are largely indistinguishable from one another.

To gauge how provocative this comment is, here is how price-to-book multiples have evolved over the last decade for the S&P 1500’s airlines and information technology sectors. If anyone can even raise such a question, it would explain some nerves over tech: The Magnificents are bearing a lot of weight. Should it become clear that they’re overvalued, there’s no shortage of alternative equity investments that look cheap by comparison. Perhaps the most dramatic illustration I’ve seen was inspired by Dhaval Joshi, also of BCA Research. Indeed, the seven Magnificent tech behemoths are now bigger by market cap than the 600 European large-cap companies in the STOXX 600. The same is also true of the S&P 500’s Information Technology sector: There are reasons for the rise of the tech platforms and the decline of Corporate Europe, of course, but can they really justify this crossing of the ways? Joshi says that “the AI mania combined with Europe’s current malaise” is “a 50-year mispricing… and opportunity.” It’s hard to disagree. No wonder investors are so nervous when a Magnificent’s results are less than perfect. I’d like to suggest reading up on Lucy Letby, the British nurse serving life in prison for murdering seven babies in her care. Nobody saw her attack any of the infants, but she was always on duty when something terrible happened; the case rested on statistics and inferences. Now, statisticians are suggesting that it wasn’t so remarkable and doesn’t prove anything, and a group of internationally respected neonatologists say all of the deaths can be attributed to natural causes, with no reason to suspect foul play. If this really is a miscarriage of justice — and I begin to think it is — then it’s one of the worst in history. For Points of Return readers, whose lives often rest on drawing statistical inferences, it’s an extraordinary cautionary tale. I strongly recommend reading the pieces I have linked; it’s upsetting, but the lessons couldn’t be more important. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Noah Feldman: Trump Is Testing Our Constitutional System. It’s Doing Fine

- Bill Dudley: Trump’s Tariffs Are Even Worse Than I Imagined

- Lionel Laurent: How Europeans Should Plan for Trump Trade Salvo

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |