|

|

Paul Bloom called me a hypocrite the other day. Well, he didn’t come out and call me names, but he asked if I felt any tension between my stated beliefs and my recent actions.

As loyal readers, you know that I dislike aspects of progressive politics. Yes, yes, I am chastened by the anti-anti-woke crowd, but my thinking is still deranged by anti-wokeness. Part of my madness is that I take issue with what some people call identity politics. Paul thus wondered if I saw any contradiction in my stance on identity politics and my recent decision to call out what I perceive as Jew hatred in psychology open letters or in my own neighbourhood. It’s a fair question—and an uncomfortable one—so I’ve been chewing on it for a few months now.

Am I a hypocrite? Because yeah, I rail against identity politics, at least privately (and on this Substack!), yet here I am talking publicly about antisemitism. At the time, I did not believe I was engaging in identity politics. But the more I thought about it, the less I could credibly hold onto this belief. Advocating for Jews in the face of antisemitism, it turns out, means stepping onto the same field I’ve spent so much time criticizing.

I sat and thought some more and ended up writing over 4,000 words on the topic. I don’t like reading or writing long Substacks, so what I’ve decided to do here is to split up my thoughts into two parts. In this first part, I want to treat identity politics seriously—not dismissively. What is it, exactly, and what are its merits? That means defining it in concrete terms, rather than leaving it as an amorphous catchphrase. Identity politics is a term that gets thrown around a lot, especially by its critics, but I have never seen a good definition or at least a good operationalization of it. I’ll also try to steelman it, meaning I will use the principle of charity to present what I think is the best case for its use. In Part II, I will criticize various elements of identity politics that I find problematic and then try to determine if my own actions are a form of identity politics, addressing my own potential hypocrisy.

The Identity Game

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, identity politics refers to:

A wide range of political activity and theorizing founded in the shared experiences of injustice of members of certain social groups. Rather than organizing solely around belief systems, programmatic manifestos, or party affiliation, identity political formations typically aim to secure the political freedom of a specific constituency marginalized within its larger context.

If that definition feels hard to follow, you’re not alone. I’m a professor and I find it a bit convoluted myself—though I’m a professor of psychology, so let’s not overstate my capacities too much. Still, there are some clear themes: marginalized groups coming together, not around a shared ideology, but around their shared experiences of injustice to push for greater freedom and recognition. It’s an okay definition, but honestly, it still feels a bit abstract and too theoretical to me. What I really want to get at is how identity politics plays out in the real world.

One way to unpack how a system is operationalized in the real world is to conceive of it as a game; let’s call it the identity game. This isn’t meant to belittle it, but to help me break down a complex idea—I’m out of my element here, just like Donny. Philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein would sometimes liken moral and political practices to games to understand these practices more deeply. Games reveal boundaries, rules, and the strategies people use to succeed. We can describe democracy, academia, or even scientific research as games to make sense of how they work. So, calling identity politics a game isn’t me being dismissive; it’s a way for me to spell out how it operates in the real world.

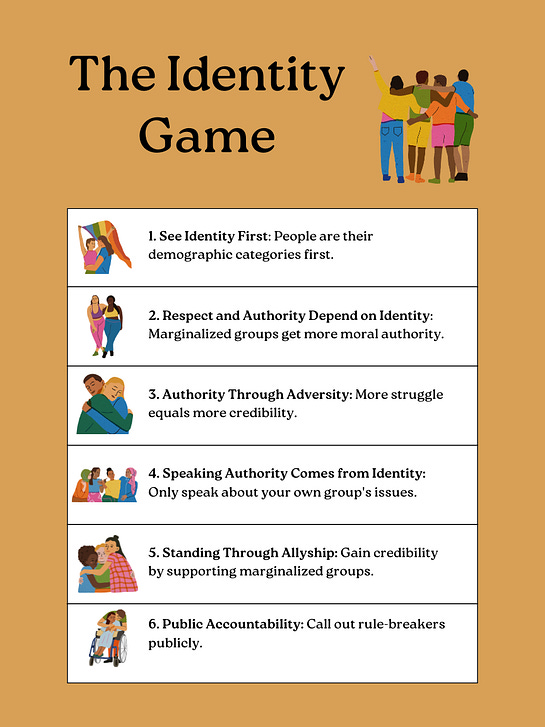

In the identity game, then, the goal might be to gain representation and influence for specific social groups, and people base their actions on implicit or explicit rules, much like they would in a board game. But unlike Settlers of Catan say, this game isn’t played for fun; it’s often a matter of survival, success, and respect. So, what are the rules of the identity game? I came up with a few, but I also collaborated with ChatGPT to help me refine and improve my list. I don’t think these rules capture the full game, but I think they’re a good start. Let me know what rules you don’t agree should be included and what rules you think I missed.

Rules of the Identity Game

1. See Identity First. The foundational rule of the game is that all social, political, and moral issues must be seen through the lens of identity. Race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and other identity categories are central to understanding all outcomes, but especially those related to power and justice. People are primarily understood through their group identities. For example, when evaluating a person’s success or failure, the focus often shifts to how their identity—whether they are a woman, a person of color, or part of the LGBTQ community—shaped their opportunities and barriers, instead of (or in addition to) their individual skills or choices.

2. Respect and Authority Depend on Identity. Identities are not treated equally in the identity game. Groups that have experienced systemic injustice are often granted more respect and deference, reflecting a reversal of traditional status hierarchies. Historically marginalized groups, then, are viewed as having greater moral authority and credibility. Intersectional identities—where someone belongs to multiple marginalized groups, like being an Indigenous woman or a queer immigrant—are often seen as especially deserving of recognition as their experiences reflect compounded marginalization. In contrast, historically privileged groups are afforded less automatic respect and authority, reflecting their longstanding advantages within the social hierarchy.

3. Authority Through Adversity. In the identity game, highlighting experiences of struggle or hardship becomes a central way to gain moral authority. Those who draw attention to their struggles, whether as individuals or as part of a group, will have their voices amplified in conversations about justice and fairness. This dynamic applies not only to historically stigmatized groups but also to individuals from privileged backgrounds who frame their experiences in terms of adversity. The emphasis on struggle creates a pathway for influence and visibility, making it a key strategy within the game.

4. Speaking Authority Comes from Identity. In the identity game, the ability to speak on an issue is determined by your identity. Only people within a specific identity group are seen as having the authority to address issues affecting that group. If a scenario involves the experiences of a particular group, only members of that group are granted the platform to discuss it, while perspectives from outside the group may be deemed illegitimate.

5. Standing Is Earned Through Acknowledgment and Allyship. In the identity game, individuals can gain moral standing by recognizing and addressing systemic inequalities. Privileged people should acknowledge their advantages, apologize for them, and use their influence to support marginalized groups. Demonstrating allyship, such as deferring to marginalized perspectives or amplifying their voices, is another way to build credibility and respect.

6. Accountability Is Enforced Through Public Criticism. In the identity game, calling out individuals or institutions for perceived insensitivity or bias is a key method of ensuring adherence to identity-based rules. Public accountability reinforces expected behaviors toward marginalized identities and signals loyalty to the group’s values.

Steelmanning the Identity Game

I think the identity game comes from a noble place. Referring to it as a game and discussing its rules and mechanics isn’t meant to diminish its importance, as I genuinely believe its ultimate goal is honorable: to make the world a more just place, especially for those who have suffered the most. In a world that systematically favors certain groups over others, these rules aim to counterbalance that historical injustice. You said it, man.

Rule 2, which grants moral authority and respect to marginalized identities, is an attempt to account for centuries of unequal privilege. When people start life with systemic disadvantages based on race, gender, or sexuality, it’s reasonable to grant them extra points—it’s a way to balance the unearned advantages many privileged identities have enjoyed for centuries. Think of this rule as a counterweight to the Eton- and Oxford-educated blue-blooded man who comes into the world with wealth, status, and privilege. It’s a way of leveling the playing field. I admire this goal.

I appreciate some of the other rules too. Rule 4, the idea that marginalized groups should have the authority to speak about their own issues, makes lots of sense. Who better to educate others about the Black experience with police than Black people themselves? When Black Americans talk about being followed in stores or pulled over while driving, they’re sharing realities most non-Black people simply haven’t faced. So, yes, it makes sense that they should have special authority on issues that others might not fully grasp. As such, we should amplify these perspectives.

There’s also wisdom in Rule 5, which encourages acknowledgment of privilege and allyship. Privilege often operates invisibly, and recognizing it helps people become aware of the systemic advantages they may have inherited. For example, an immigrant from Germany might see themselves as self-made after launching a successful business. Yet, they may still benefit from unearned privileges tied to the colour of their skin or their Western education. Meanwhile, an equally hardworking and intelligent immigrant from Eritrea might face far more obstacles, encountering biases and barriers that complicate their path to success.

Acknowledging these dynamics isn’t about diminishing individual achievements; it’s about recognizing that some people begin the race a few paces ahead. And this is where allyship comes in: when done thoughtfully, it allows privileged individuals to use their influence to support those who’ve been marginalized. When rooted in understanding and respect, allyship can amplify marginalized voices and therefore help level the playing field for those who are born into less privilege.

While I really don’t like Rule 6, publicly calling out offenders of these rules, I admit that it has a place. If someone is biased or abuses their power, sometimes the only way to get them to stop and correct their behaviour is by publicly shaming them. Two examples that come to mind are the #MeToo movement and the Open Science movement (of which I am an advocate). By bringing attention to terrible abuses of power, such as Harvey Weinstein spending decades dangling the prospect of starring in his films in exchange for sex, we changed our culture for the better. While we still have a long way to go, this public awareness has fostered a growing culture of consent.